These were, of course, predictable: a host of cancers, burnt skin and birth defects in the next generation. One is reminded of the medical experiments conducted by the Nazis on “lesser peoples.”

Thursday, February 9, 2017

Lily pads and the Spratlys

Lily pads and the Spratlys

· Written by Ken Fuller

· Tuesday, 07 February 2017 00:00

· Daily Tribune

Anyone who wants to view the South China Sea controversy in a wholly new context could do worse than watch “The Coming War on China,” written, produced and directed by John Pilger, released in theaters last year and now available on DVD.

Pilger’s wholly convincing thesis is that the USA has for several years been assembling a huge war machine directed at China and that unless ordinary people in the Asia-Pacific and the USA take a firm stand against it, it will sooner or later be used, with potentially terminal consequences for the planet.

The film, almost two hours in length, begins with a comprehensive look at the US nuclear testing program in the Marshall Islands, which suffered the equivalent of a bomb of Hiroshima magnitude every day for12 years. (According to a November 2015 Washington Post piece, 67 tests between 1946 and 1958 resulted in an average of 1.6 Hiroshima bombs per day).

Just as ghastly as the tests was US treatment of the islanders. Residents of Rongelap atoll were relocated in 1954, two days after a huge detonation, a thousand times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb, on Bikini atoll. In 1957, they were told that Rongelap was now safe and were allowed to return.

The US authorities not only knew that it was not safe, but planned to use these returnees (referred to as “savages” in at least one US newsreel) as guinea-pigs for the study of the effects of radiation on humans.

These were, of course, predictable: a host of cancers, burnt skin and birth defects in the next generation. One is reminded of the medical experiments conducted by the Nazis on “lesser peoples.”

These were, of course, predictable: a host of cancers, burnt skin and birth defects in the next generation. One is reminded of the medical experiments conducted by the Nazis on “lesser peoples.”

After a review of the history of US-China relations, Pilger takes a look at today’s China. “The truth” he says, “is that China has matched the United States at its own great game of capitalism. And that is unforgivable.” China’s goals, says social scientist Eric Li, are very modest: it doesn’t want to dominate the world, or even the Asia-Pacific, but it does want to prevent the US from lording it over the region and preventing China from occupying its proper place in the world.

In Okinawa, the USA has 32 military installations and some 25,000 troops (around half of those in the whole of Japan). Ten years after World War II, the US’s “bulldozer and bayonets” campaign seized “prime agricultural land, burned farmhouses and killed livestock.” Small wonder, then, that a vibrant opposition to the military occupation exists to this day.

In December 2014, a new Okinawa governor was overwhelmingly elected on a pledge to stop the construction of a new base, but the Tokyo government is resisting this challenge to its authority.

On Okinawa, there have been 44 accidents involving US aircraft, and prostitution and sexual crimes are a problem. In 1970, the latter gave rise to a major riot during which US personnel were dragged from their cars, which were then burned. Recent opposition to the military occupation has been spurred by the rape and murder of a young woman for which, in June 2016, a US contractor, a former Marine, was charged.

Okinawa also provides an example of the more serious dangers that come with the military bases. In the Cold War, nuclear weapons were secretly installed, and during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis the order was given to launch the missiles, most of which were targeted on China (which was not a party to the Cuban crisis).

Thankfully, a sane duty officer queried the order, ordering that anyone attempting to launch should be shot. The major who had issued the launch order was discretely dismissed from the service.

The Korean island of Jeju, despite being declared an “island of world peace,” hosts “one of the most provocative military bases in the world, less than 400 miles from Shanghai.”

Every day for a decade, a Catholic mass has blocked the gates to the base. Father Mun Jeong-hyeon has no doubts about the purpose of the new base: to aid US domination of the Pacific and to isolate China.

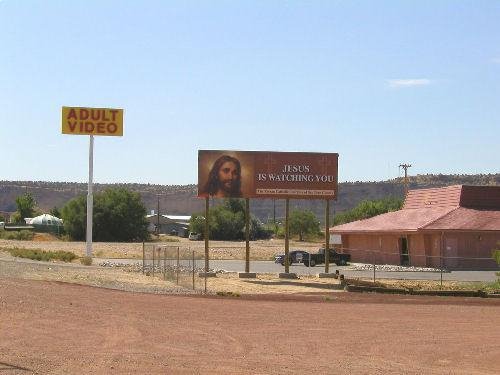

Outside of the USA, Washington has 1,000 bases across all continents. Lately, these have taken the form of “lily pads,” where US installations operate, often secretly, from bases of the host country. This has resulted, says Pilger, in the USA having “a secret army in 147 countries.”

There exists a “noose of bases right around China…a provocation to war.” Asks University of Missouri’s Stephen Starr: “What’s the purpose? When are we going to stop this process before it starts a war? And then, if the war starts, where does that end?” Starr says that scientists concerned about the effects of nuclear war, which could end human life on this planet, made several requests to discuss these concerns with the Obama administration, only to be turned away.

Anyone who thinks those scientists might have better luck with Trump should probably not be reading this column. Trump has talked of better relations with Russia (although, given some of his appointments, even this might be in doubt), but on China he seems likely to add to the chorus of saber-rattling.

And, of course, the Philippines will soon have its own US “lily pads,” courtesy of the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement signed by former President Aquino. Despite President Duterte’s earlier objections to the presence of US troops, Defense Secretary Lorenzana recently told a news conference that “EDCA is still on.”

Pilger suggests that Chinese activity in the South China Sea must be viewed in the context of the “noose of bases” with which it is surrounded. The corollary of this, of course, is that the presence of “lily pads” in the Philippines is hardly likely to contribute to a resolution of the Spratlys problem.