If there is "sovereignty;" why is smoking allowed, to the detriment of workers' health, in these casinos?

What kind of perverted "sovereignty" is it when casino workers have no rights?

http://www.economist.com/node/21552208

American Indians

Gambling on nation-building

Tribes are at last becoming sovereign in more than theory, with mixed results

Born in a wikiup, a traditional Apache brush wigwam, and brought up on stories of bloodshed between his forebears and the white man, Mr Lupe has been in tribal government, off and on, since 1964. His career thus spans several historic changes for Indian tribes, each of which affirmed and increased their sovereignty.

“When I was first elected, I received no financial reports, no letters, they all went over there,” he recalls, pointing across the street to a branch of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), the federal agency that handles relations with tribes. “Over the years I took their power away.” Then he flips his middle finger in the BIA's direction. “I'm not responsible to you, I'm a sovereign nation.”

That sovereignty is still a topic of discussion at all should be surprising. America's constitution names three sovereigns: the federal government, states and tribes. The “treaties” America signed with tribes in the 18th and 19th centuries also implied sovereign parties. Tribes could not keep armies or devise a currency, but they could issue their own passports, as the Iroquois have famously done (which made their lacrosse team miss a tournament in 2010, after Britain refused to recognise the documents). The Iroquois, the Sioux and the Ojibwe (Chippewa), even separately declared war on Germany in 1941.

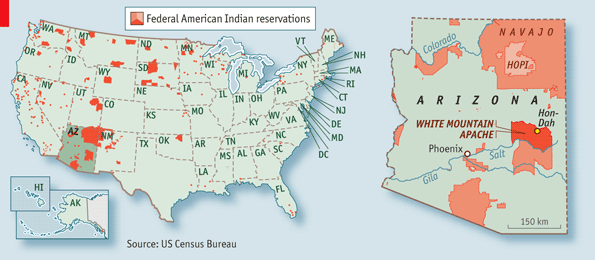

But sovereignty has at least three pieces, says Manley Begay at the Harvard Project on American Indian Economic Development, a research group. First, there is “inherent” sovereignty. Mr Begay's Navajo, for example, consider their sovereignty a sacred gift from their Holy People. But there are also legal and de facto sovereignty, and the federal government, for most of American history, honoured neither. It considered treaties merely a tool to take land from the tribes. Its real policy towards Indians before 1851 was to remove them. After 1851, when the first modern Indian reservations were created, the policy was to contain them in what one Indian author has called “red ghettos” for their widespread poverty, unemployment, alcoholism and crime.

In theory, this changed in 1934 with an act of Congress nicknamed the Indian New Deal. It endorsed a degree of self-rule for Indian tribes, while urging them to form tribal constitutions similar to America's own, with elections, courts and so forth. But in practice federal paternalism continued. Native American religions, for example, were persecuted until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 at last put a stop to it. Above all, the BIA (originally part of the War Department but nowadays part of Interior) made all decisions of economic consequence.

Those memories still get a rise out of Mr Lupe. Ultimately, sovereignty is power over land, he says. To the white man, he thinks, land is just “real estate”. But in Apache the word for land is also the one for mind: “So I point to my mind, I also point to my land,” he says, as his index finger moves from his forehead to the ground. It so happens that his tribe's land is exceptional: the Salt River Canyon is as beautiful as the Grand Canyon, but without the tourists, and above it stretch endless forests of ponderosa pines. The right to fish, hunt, log and do whatever else they please there is what Mr Lupe and his ancestors have fought for. The only difference, he says, is that “We now go to war with pens, not bows and arrows.”

A roll of the dice

The biggest step towards de facto sovereignty came in 1975, with the Indian Self-Determination Act. It began the transfer of administration from the BIA to the tribal governments. Mr Begay calls the act “up there with the Iron Curtain falling down, with apartheid falling apart” in its importance. It also made possible the biggest economic change of the past century, the entry of tribes into the gaming business.

This began with the Seminole tribe in Florida and the Cabazon Mission Band of Indians, a tiny tribe in southern California. The Seminole took their case for running a bingo parlour to a federal appeals court, and won it in 1981. Around the same time the Cabazon Band opened poker and bingo rooms on their reservation, illegal under state law. The police raided the reservation, and a legal case began that wound its way as far as the Supreme Court. In 1987 the court decided that tribes, being sovereign, could not be barred from running casinos. The next year Congress wrote a law that explicitly allowed Indian gambling, as long as the proceeds were used to promote “tribal economic development”.

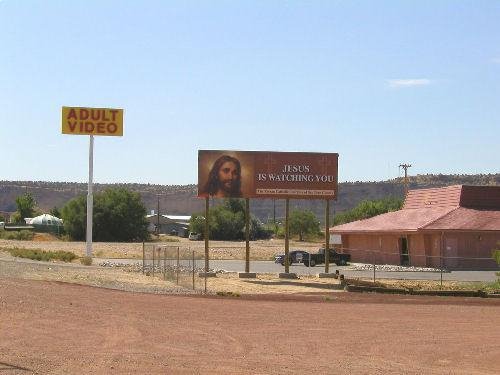

Soon tribes all over the country built casinos. Mr Lupe's Apache opened theirs in 1993. Called Hon-Dah (“Welcome” in Apache), it is, like most casinos in America, a somewhat depressing place, with people in track suits yanking on slot machines in clouds of cigarette smoke.

In 2010, estimates Alan Meister, an economist, Indian casinos took in $26.7 billion, about 44% of America's total casino revenue. Almost half of the tribes—239 out of the 565—are now at it. A few, including the Cabazon Band, are rolling in money, whereas others make hardly anything. The key, not surprisingly, is location. Casinos on reservations near cities (the Cabazon are near Palm Springs) get many customers, whereas those in the middle of nowhere (the majority, like Hon-Dah) get few.

For the tribes with lucrative casinos, gambling has become the biggest thing since the fur trade of the 19th century, says David Wilkins, a Lumbee and professor of American-Indian studies at the University of Minnesota. When the proceeds are used wisely—to build schools, provide health care, and so forth—gambling can indeed help with tribal nation-building, he says.

But casinos also bring problems. Some tribes consider gambling a vice. This is why the Hopi, for instance, have rejected gambling, and why the Navajo repeatedly voted against it in referendums before grudgingly accepting it for the revenues it brought in. In other cases, gambling income perversely reinforces a culture of dependency, as some tribal members wait passively for their profit share.

Indirectly the casinos have also highlighted some bizarre, sometimes unsavoury, aspects of tribal sovereignty. One of the biggest problems has always been deciding who is or is not a member. Most tribes do this with blood-quantum laws. An individual must prove that, say, a quarter, an eighth, or a sixteenth of his “blood” is from a given tribe.

Casino money has brought out the perversity in these rules. In California alone more than 2,500 Indians have been “dis-enrolled”—ie, cast out—from their tribes because political enemies or greedy administrators have suddenly discovered doubts about distant bloodlines. The motive is to share gambling revenues among fewer members. For the outcasts, this can mean losing tribal housing, education, welfare and sometimes cash payments, not to mention identity and community.

Pain and progress

The bigger question is whether sovereignty in general and gambling in particular have, on balance, improved the lot of tribes. Unfortunately, any progress is patchy and slow. In the 2010 census 28% of American Indians were poor, compared with 15% of the whole American population. Their median household income was $35,062, compared with $50,046 for all Americans. They are, on average, less educated and less likely to have health insurance. Most of the 2.9m American Indians now live in cities, including many of those who are better off. So poverty on the 334 reservations (not all tribes have one) is worse than these numbers suggest.

Unemployment is astronomically high. Mr Lupe estimates that it is 80% for the White Mountain Apache (others estimate it at nearer 65% on that reservation). Alcohol and drug abuse are endemic, as are obesity and diabetes. Violent-crime rates on reservations are twice the national average, according to the Justice Department. American-Indian women are four times as likely to be raped and ten times as likely to be murdered as white American women.

When it comes to governance, American Indians are still all too likely to make news of the wrong sort. The Chukchansi of California, near Yosemite, spent the first part of this year brawling over control of their tribal council, with one side cracking the locks and smashing the windows of the government building to break in, while the other side cut the building's electricity and fumigated it with bear spray. (As it happens, the tribe runs a successful casino, and the dispute had started over dis-enrolments of members.)

Even Mr Lupe has been involved in antics of this sort. Last December the tribe's council (including two of Mr Lupe's cousins and one nephew) voted to suspend Mr Lupe as chairman, alleging corruption and megalomania. Mr Lupe ignored the motion vote, suggesting that corruption is instead to be found among the council members, and that the Apache constitution has no concept of suspension. A judge was fired. The police chief who had been instructed to evict Mr Lupe thought better of it. Mr Lupe remains well ensconced. A tribal lawyer says that Apache government does not have distinct branches as America's does, but values consensus.

So the record is far from clear. Mr Lupe's Apache (there are other Apache tribes nearby) have their casino, some timber logging and a decent ski resort to boot. And they are surrounded by stunning natural beauty. But they are still quite poor.

They are also more sovereign now than they have been since Geronimo's day. And yet, laments Mr Lupe, Apache culture is still under threat. Over half of the older members speak Apache, he says, but fewer than 10% of the young do. Indeed, of hundreds of American-Indian languages spoken when Europeans arrived, only about 150 survive, and only three (Dakota, Dene and Ojibwe) have viable communities of speakers. Dissolution into the American mainstream, of course, has always been a spectre, even if it is no longer federal policy. And yet, as David Treuer, an Ojibwe and the author of “Rez Life”, puts it with pride, “We stubbornly continue to exist.”