The fact is, people don't trust scientists and their conclusions because so many scientists have sold themselves to big business.

Science is not being used for the people in this country.

Science has been used to bolster the corporate bottom line: profits.

Just look at science and the university.

Research has been corrupted by the corporate drive for profits.

It is relatively easy for big business to buy a "scientific" opinion to support anything that can make a profit--- from militarism to the kind of food we eat.

Scientists, for the most part, don't use their research to advance peace, anti-racism, the well-being of people and the environment. Science has been used to expand Wall Street's profits. This is why people don't trust scientists and their views, opinions and research.

Scientists do nothing to bring their ideas and research into the public square where people have a choice to think about any of this.

Scientists don't come into the public square to defend their ideas, opinions and research; they remain aloof of the people and then we get articles like this outlining the rift between "regular" people and scientists.

This rotten capitalist social and economic system corrupts science just like it corrupts politics, health care, sports, culture and everything else. And then we wonder why people doubt scientific reasoning?

We need a social and economic system, socialism, where science is for the good of people and the environment.When people understand science is on their side, not Wall Street's side, people will support science.

Most important is we need a scientific community squarely on the side of peace--- in opposition to militarization and these dirty imperialist wars.

Alan L. Maki

Poll:

Poll Reveals Rift Between Scientists, Regular Folks

When it comes to food, energy, and education, Americans don't follow experts' lead.

Recent

outbreaks of measles have been tied to children who haven't been

vaccinated. Many people still believe that childhood vaccinations are

dangerous, despite scientific evidence to the contrary.

Photograph by Joe Raedle, Getty

Dan Vergano

Published January 29, 2015

What do the International Space Station and bioengineered

fuels have in common? They're about the only technological advances that

both scientists and the American public actually like.

On most other scientific matters, a widespread "opinion gap" splits the experts from everyday folks, pollsters at the

Pew Research Center reported Thursday.

The rift persists in long-running issues such as the causes of climate

change and the safety of nuclear power. And it crops up in the news

today in battles over outbreaks of measles tied to children who haven't

been vaccinated.

Scientists say this opinion gap points to

shortcomings in their own skills at reaching out to the public and to

deficits in science education. On the last point, at least, the public

agrees, with majorities on both sides rating U.S. education as average

at best.

That's bad news for the future, says American Association for the Advancement of Science head

Alan Leshner, if Americans want to keep enjoying the benefits of science.

"There is a disconnect between the way the public

perceives science and the way that scientists see science," says

Leshner, whose Washington D.C.-based organization collaborated with Pew

on the polling. "Scientists need to do something to turn this around."

In an editorial in the journal

Science,

Leshner called on scientists to personally stem a swelling

"unbridgeable chasm" in attitudes between researchers and the taxpayers

who largely fund essential research.

Mind the Gap

In a head-to-head comparison of expert and

everyday attitudes, the two new polls asked 2,002 U.S. adults and 3,748

AAAS members (described as "a broad-ranging group of professionally

engaged scientists") identical questions about their views on scientific

achievement, education, and controversial issues.

"People are still mostly positive about science,"

but compared with five years ago, "we are seeing a slight souring of the

views," says Pew polling expert

Cary Funk. "When you look across the questions, you are struck by large differences in citizens and scientists."

On the safety of genetically modified food and

pesticides, for example, experts and the public differed by 40

percentage points or more in their approval, with the majority of

scientists saying GMO foods are safe to eat. On their beliefs in

human-caused climate change and human evolution, the groups differed by

more than 30 percentage points. Differences nearly as large are seen on

vaccination, animal research, and offshore oil drilling.

Emily M. Eng, NG Staff. Source: Pew Research Center

"We are seeing the gaps as larger now across a large set of issues," Funk says, compared to past polls.

Political Science

Though scientists point to a lack of public

understanding of science, "having scientists speak at Kiwanis club

meetings is not going to change a lot of people's views about science,"

says polling expert

Jon Miller of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The survey results don't differ a great deal from

past polls, but this only reinforces anxiety over the future of science,

Miller adds. Support for research has gone from a bedrock American

principle to one suffering fissures from political fistfights over human

evolution, embryonic stem cells, climate change, and other issues.

"A lot of scientific issues have become

politicized," Miller says. "I think this report is kind of tiptoeing

around that reality, where the [U.S.] Republican party has sought

political support from voters with religious views who are often hostile

to science."

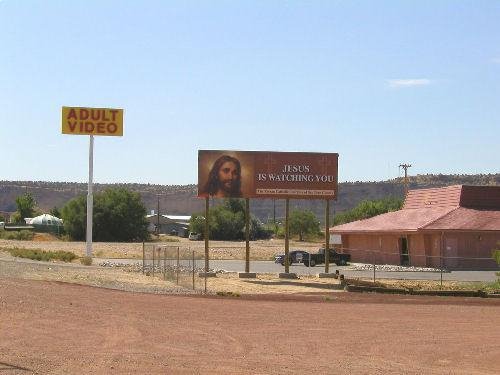

To his point, an

American Sociological Review study also

reported on Thursday that

roughly one in five U.S. adults is deeply religious and accepts

astronomy, radioactivity, and genetics as settled science but rejects

human evolution and the big bang. These are high-income, well-educated

people who are "scientifically literate" and view science favorably,

according to study lead author

Timothy O'Brien of the

University of Evansville in Indiana. They just toss overboard science that clashes with literal readings of the Bible.

Over the last decade, public opinion researchers such as Yale's

Dan Kahan have found that people's views on many scientific issues,

such as climate and evolution, are largely driven by their cultural views. Sociologist

Robert Brulle of Drexel University in Philadelphia likewise found that when

political leaders change their views on climate change, voters are more likely to be swayed than they are by the voices of scientists.

Leshner, however, disagrees. "Political leaders

don't carry the same kind of credibility that well-informed scientists

do," he says.

He argues that scientists can better sway public

opinion by making the case for science in smaller venues, such as

retirement communities or library groups, instead of the traditional

lecture hall. "It is important that the public understands that

scientists are people too."

Why Do Many Reasonable People Doubt Science?

We live in an age when all manner of scientific knowledge—from climate change to vaccinations—faces furious opposition.

Some even have doubts about the moon landing.

By Joel Achenbach

Photographs by Richard Barnes

There’s a scene in Stanley Kubrick’s comic masterpiece

Dr. Strangelove

in which Jack D. Ripper, an American general who’s gone rogue and

ordered a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union, unspools his paranoid

worldview—and the explanation for why he drinks “only distilled water,

or rainwater, and only pure grain alcohol”—to Lionel Mandrake, a

dizzy-with-anxiety group captain in the Royal Air Force.

Ripper: Have you ever heard of a thing called fluoridation? Fluoridation of water?

Mandrake: Ah, yes, I have heard of that, Jack. Yes, yes.

Ripper: Well, do you know what it is?

Mandrake: No. No, I don’t know what it is. No.

Ripper: Do you realize that fluoridation is the most monstrously conceived and dangerous communist plot we have ever had to face?

The movie came out in 1964, by which time the health

benefits of fluoridation had been thoroughly established, and

antifluoridation conspiracy theories could be the stuff of comedy. So

you might be surprised to learn that, half a century later, fluoridation

continues to incite fear and paranoia. In 2013 citizens in Portland,

Oregon, one of only a few major American cities that don’t fluoridate

their water, blocked a plan by local officials to do so. Opponents

didn’t like the idea of the government adding “chemicals” to their

water. They claimed that fluoride could be harmful to human health.

Actually fluoride is a natural mineral that, in the weak

concentrations used in public drinking water systems, hardens tooth

enamel and prevents tooth decay—a cheap and safe way to improve dental

health for everyone, rich or poor, conscientious brusher or not. That’s

the scientific and medical consensus.

To which some people in Portland, echoing antifluoridation activists around the world, reply: We don’t believe you.

We live in an age when all manner of scientific knowledge—from the

safety of fluoride and vaccines to the reality of climate change—faces

organized and often furious opposition. Empowered by their own sources

of information and their own interpretations of research, doubters have

declared war on the consensus of experts. There are so many of these

controversies these days, you’d think a diabolical agency had put

something in the water to make people argumentative. And there’s so much

talk about the trend these days—in books, articles, and academic

conferences—that science doubt itself has become a pop-culture meme. In

the recent movie

Interstellar, set in a futuristic, downtrodden

America where NASA has been forced into hiding, school textbooks say the

Apollo moon landings were faked.

In a sense all this is not surprising. Our lives are permeated by

science and technology as never before. For many of us this new world is

wondrous, comfortable, and rich in rewards—but also more complicated

and sometimes unnerving. We now face risks we can’t easily analyze.

We’re asked to accept, for example, that it’s safe to eat food

containing genetically modified organisms (GMOs) because, the experts

point out, there’s no evidence that it isn’t and no reason to believe

that altering genes precisely in a lab is more dangerous than altering

them wholesale through traditional breeding. But to some people the very

idea of transferring genes between species conjures up mad scientists

running amok—and so, two centuries after Mary Shelley wrote

Frankenstein, they talk about Frankenfood.

The world crackles with real and imaginary hazards, and

distinguishing the former from the latter isn’t easy. Should we be

afraid that the Ebola virus, which is spread only by direct contact with

bodily fluids, will mutate into an airborne superplague? The scientific

consensus says that’s extremely unlikely: No virus has ever been

observed to completely change its mode of transmission in humans, and

there’s zero evidence that the latest strain of Ebola is any different.

But type “airborne Ebola” into an Internet search engine, and you’ll

enter a dystopia where this virus has almost supernatural powers,

including the power to kill us all.

In this bewildering world we have to decide what to believe and

how to act on that. In principle that’s what science is for. “Science is

not a body of facts,” says geophysicist Marcia McNutt, who once headed

the U.S. Geological Survey and is now editor of

Science, the

prestigious journal. “Science is a method for deciding whether what we

choose to believe has a basis in the laws of nature or not.” But that

method doesn’t come naturally to most of us. And so we run into trouble,

again and again.

Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

Square Intuitions Die Hard

That

the Earth is round has been known since antiquity—Columbus knew he

wouldn’t sail off the edge of the world—but alternative geographies

persisted even after circumnavigations had become common. This 1893 map

by Orlando Ferguson, a South Dakota businessman, is a loopy variation on

19th-century flat-Earth beliefs. Flat-Earthers held that the planet was

centered on the North Pole and bounded by a wall of ice, with the sun,

moon, and planets a few hundred miles above the surface. Science often

demands that we discount our direct sensory experiences—such as seeing

the sun cross the sky as if circling the Earth—in favor of theories that

challenge our beliefs about our place in the universe.

The trouble goes way back, of course. The scientific method

leads us to truths that are less than self-evident, often mind-blowing,

and sometimes hard to swallow. In the early 17th century, when Galileo

claimed that the Earth spins on its axis and orbits the sun, he wasn’t

just rejecting church doctrine. He was asking people to believe

something that defied common sense—because it sure looks like the sun’s

going around the Earth, and you can’t feel the Earth spinning. Galileo

was put on trial and forced to recant. Two centuries later Charles

Darwin escaped that fate. But his idea that all life on Earth evolved

from a primordial ancestor and that we humans are distant cousins of

apes, whales, and even deep-sea mollusks is still a big ask for a lot of

people. So is another 19th-century notion: that carbon dioxide, an

invisible gas that we all exhale all the time and that makes up less

than a tenth of one percent of the atmosphere, could be affecting

Earth’s climate.

Even when we intellectually accept these precepts of science, we

subconsciously cling to our intuitions—what researchers call our naive

beliefs. A recent study by Andrew Shtulman of Occidental College showed

that even students with an advanced science education had a hitch in

their mental gait when asked to affirm or deny that humans are descended

from sea animals or that Earth goes around the sun. Both truths are

counterintuitive. The students, even those who correctly marked “true,”

were slower to answer those questions than questions about whether

humans are descended from tree-dwelling creatures (also true but easier

to grasp) or whether the moon goes around the Earth (also true but

intuitive). Shtulman’s research indicates that as we become

scientifically literate, we repress our naive beliefs but never

eliminate them entirely. They lurk in our brains, chirping at us as we

try to make sense of the world.

Most of us do that by relying on personal experience and

anecdotes, on stories rather than statistics. We might get a

prostate-specific antigen test, even though it’s no longer generally

recommended, because it caught a close friend’s cancer—and we pay less

attention to statistical evidence, painstakingly compiled through

multiple studies, showing that the test rarely saves lives but triggers

many unnecessary surgeries. Or we hear about a cluster of cancer cases

in a town with a hazardous waste dump, and we assume pollution caused

the cancers. Yet just because two things happened together doesn’t mean

one caused the other, and just because events are clustered doesn’t mean

they’re not still random.

We have trouble digesting randomness; our brains crave pattern and

meaning. Science warns us, however, that we can deceive ourselves. To

be confident there’s a causal connection between the dump and the

cancers, you need statistical analysis showing that there are many more

cancers than would be expected randomly, evidence that the victims were

exposed to chemicals from the dump, and evidence that the chemicals

really can cause cancer.

Photo: Bettman/Corbis

Evolution on Trial

In

1925 in Dayton, Tennessee, where John Scopes was standing trial for

teaching evolution in high school, a creationist bookseller hawked his

wares. Modern biology makes no sense without the concept of evolution,

but religious activists in the United States continue to demand that

creationism be taught as an alternative in biology class. When science

conflicts with a person’s core beliefs, it usually loses.

Even for scientists, the scientific method is a hard discipline.

Like the rest of us, they’re vulnerable to what they call confirmation

bias—the tendency to look for and see only evidence that confirms what

they already believe. But unlike the rest of us, they submit their ideas

to formal peer review before publishing them. Once their results are

published, if they’re important enough, other scientists will try to

reproduce them—and, being congenitally skeptical and competitive, will

be very happy to announce that they don’t hold up. Scientific results

are always provisional, susceptible to being overturned by some future

experiment or observation. Scientists rarely proclaim an absolute truth

or absolute certainty. Uncertainty is inevitable at the frontiers of

knowledge.

Sometimes scientists fall short of the ideals of the scientific

method. Especially in biomedical research, there’s a disturbing trend

toward results that can’t be reproduced outside the lab that found them,

a trend that has prompted a push for greater transparency about how

experiments are conducted. Francis Collins, the director of the National

Institutes of Health, worries about the “secret sauce”—specialized

procedures, customized software, quirky ingredients—that researchers

don’t share with their colleagues. But he still has faith in the larger

enterprise.

“Science will find the truth,” Collins says. “It may get it wrong

the first time and maybe the second time, but ultimately it will find

the truth.” That provisional quality of science is another thing a lot

of people have trouble with. To some climate change skeptics, for

example, the fact that a few scientists in the 1970s were worried (quite

reasonably, it seemed at the time) about the possibility of a coming

ice age is enough to discredit the concern about global warming now.

Last fall the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,

which consists of hundreds of scientists operating under the auspices of

the United Nations, released its fifth report in the past 25 years.

This one repeated louder and clearer than ever the consensus of the

world’s scientists: The planet’s surface temperature has risen by about

1.5 degrees Fahrenheit in the past 130 years, and human actions,

including the burning of fossil fuels, are extremely likely to have been

the dominant cause of the warming since the mid-20th century. Many

people in the United States—a far greater percentage than in other

countries—retain doubts about that consensus or believe that climate

activists are using the threat of global warming to attack the free

market and industrial society generally. Senator James Inhofe of

Oklahoma, one of the most powerful Republican voices on environmental

matters, has long declared global warming a hoax.

The idea that hundreds of scientists from all over the world would

collaborate on such a vast hoax is laughable—scientists love to debunk

one another. It’s very clear, however, that organizations funded in part

by the fossil fuel industry have deliberately tried to undermine the

public’s understanding of the scientific consensus by promoting a few

skeptics.

The news media give abundant attention to such mavericks,

naysayers, professional controversialists, and table thumpers. The media

would also have you believe that science is full of shocking

discoveries made by lone geniuses. Not so. The (boring) truth is that it

usually advances incrementally, through the steady accretion of data

and insights gathered by many people over many years. So it has been

with the consensus on climate change. That’s not about to go poof with

the next thermometer reading.

But industry PR, however misleading, isn’t enough to explain why

only 40 percent of Americans, according to the most recent poll from the

Pew Research Center, accept that human activity is the dominant cause

of global warming.

The “science communication problem,” as it’s blandly called by the

scientists who study it, has yielded abundant new research into how

people decide what to believe—and why they so often don’t accept the

scientific consensus. It’s not that they can’t grasp it, according to

Dan Kahan of Yale University. In one study he asked 1,540 Americans, a

representative sample, to rate the threat of climate change on a scale

of zero to ten. Then he correlated that with the subjects’ science

literacy. He found that higher literacy was associated with stronger

views—at both ends of the spectrum. Science literacy promoted

polarization on climate, not consensus. According to Kahan, that’s

because people tend to use scientific knowledge to reinforce beliefs

that have already been shaped by their worldview.

Americans fall into two basic camps, Kahan says. Those with a more

“egalitarian” and “communitarian” mind-set are generally suspicious of

industry and apt to think it’s up to something dangerous that calls for

government regulation; they’re likely to see the risks of climate

change. In contrast, people with a “hierarchical” and “individualistic”

mind-set respect leaders of industry and don’t like government

interfering in their affairs; they’re apt to reject warnings about

climate change, because they know what accepting them could lead to—some

kind of tax or regulation to limit emissions.

In the U.S., climate change somehow has become a litmus test that

identifies you as belonging to one or the other of these two

antagonistic tribes. When we argue about it, Kahan says, we’re actually

arguing about who we are, what our crowd is. We’re thinking, People like

us believe this. People like that do not believe this. For a

hierarchical individualist, Kahan says, it’s not irrational to reject

established climate science: Accepting it wouldn’t change the world, but

it might get him thrown out of his tribe.

“Take a barber in a rural town in South Carolina,” Kahan has

written. “Is it a good idea for him to implore his customers to sign a

petition urging Congress to take action on climate change? No. If he

does, he will find himself out of a job, just as his former congressman,

Bob Inglis, did when he himself proposed such action.”

Science appeals to our rational brain, but our beliefs are

motivated largely by emotion, and the biggest motivation is remaining

tight with our peers. “We’re all in high school. We’ve never left high

school,” says Marcia McNutt. “People still have a need to fit in, and

that need to fit in is so strong that local values and local opinions

are always trumping science. And they will continue to trump science,

especially when there is no clear downside to ignoring science.”

Meanwhile the Internet makes it easier than ever for climate

skeptics and doubters of all kinds to find their own information and

experts. Gone are the days when a small number of powerful

institutions—elite universities, encyclopedias, major news

organizations, even

National Geographic—served as gatekeepers of

scientific information. The Internet has democratized information, which

is a good thing. But along with cable TV, it has made it possible to

live in a “filter bubble” that lets in only the information with which

you already agree.

How to penetrate the bubble? How to convert climate skeptics?

Throwing more facts at them doesn’t help. Liz Neeley, who helps train

scientists to be better communicators at an organization called Compass,

says that people need to hear from believers they can trust, who share

their fundamental values. She has personal experience with this. Her

father is a climate change skeptic and gets most of his information on

the issue from conservative media. In exasperation she finally

confronted him: “Do you believe them or me?” She told him she believes

the scientists who research climate change and knows many of them

personally. “If you think I’m wrong,” she said, “then you’re telling me

that you don’t trust me.” Her father’s stance on the issue softened. But

it wasn’t the facts that did it.

If you’re a rationalist, there’s something a little

dispiriting about all this. In Kahan’s descriptions of how we decide

what to believe, what we decide sometimes sounds almost incidental.

Those of us in the science-communication business are as tribal as

anyone else, he told me. We believe in scientific ideas not because we

have truly evaluated all the evidence but because we feel an affinity

for the scientific community. When I mentioned to Kahan that I fully

accept evolution, he said, “Believing in evolution is just a description

about you. It’s not an account of how you reason.”

Maybe—except that evolution actually happened. Biology is

incomprehensible without it. There aren’t really two sides to all these

issues. Climate change is happening. Vaccines really do save lives.

Being right does matter—and the science tribe has a long track record of

getting things right in the end. Modern society is built on things it

got right.

Doubting science also has consequences. The people who believe

vaccines cause autism—often well educated and affluent, by the way—are

undermining “herd immunity” to such diseases as whooping cough and

measles. The anti-vaccine movement has been going strong since the

prestigious British medical journal the

Lancet published a study

in 1998 linking a common vaccine to autism. The journal later retracted

the study, which was thoroughly discredited. But the notion of a

vaccine-autism connection has been endorsed by celebrities and

reinforced through the usual Internet filters. (Anti-vaccine activist

and actress Jenny McCarthy famously said on the

Oprah Winfrey Show, “The University of Google is where I got my degree from.”)

In the climate debate the consequences of doubt are likely global

and enduring. In the U.S., climate change skeptics have achieved their

fundamental goal of halting legislative action to combat global warming.

They haven’t had to win the debate on the merits; they’ve merely had to

fog the room enough to keep laws governing greenhouse gas emissions

from being enacted.

Some environmental activists want scientists to emerge from their

ivory towers and get more involved in the policy battles. Any scientist

going that route needs to do so carefully, says Liz Neeley. “That line

between science communication and advocacy is very hard to step back

from,” she says. In the debate over climate change the central

allegation of the skeptics is that the science saying it’s real and a

serious threat is politically tinged, driven by environmental activism

and not hard data. That’s not true, and it slanders honest scientists.

But it becomes more likely to be seen as plausible if scientists go

beyond their professional expertise and begin advocating specific

policies.

It’s their very detachment, what you might call the

cold-bloodedness of science, that makes science the killer app. It’s the

way science tells us the truth rather than what we’d like the truth to

be. Scientists can be as dogmatic as anyone else—but their dogma is

always wilting in the hot glare of new research. In science it’s not a

sin to change your mind when the evidence demands it. For some people,

the tribe is more important than the truth; for the best scientists, the

truth is more important than the tribe.

Scientific thinking has to be taught, and sometimes it’s not

taught well, McNutt says. Students come away thinking of science as a

collection of facts, not a method. Shtulman’s research has shown that

even many college students don’t really understand what evidence is. The

scientific method doesn’t come naturally—but if you think about it,

neither does democracy. For most of human history neither existed. We

went around killing each other to get on a throne, praying to a rain

god, and for better and much worse, doing things pretty much as our

ancestors did.

Now we have incredibly rapid change, and it’s scary sometimes.

It’s not all progress. Our science has made us the dominant organisms,

with all due respect to ants and blue-green algae, and we’re changing

the whole planet. Of course we’re right to ask questions about some of

the things science and technology allow us to do. “Everybody should be

questioning,” says McNutt. “That’s a hallmark of a scientist. But then

they should use the scientific method, or trust people using the

scientific method, to decide which way they fall on those questions.” We

need to get a lot better at finding answers, because it’s certain the

questions won’t be getting any simpler.

Washington Post science writer Joel Achenbach has contributed to

National Geographic since 1998. Photographer Richard Barnes’s last feature was the September 2014 cover story on

Nero.