A tale of corporate capture in MN

Crossposted from Lex Horan's blog at PANNA

Leave a twig for the birds to perch on... don't let the capitalists do your thinking for you... if you are in the neighborhood, stop on in; the coffee is always hot and the cookie jar is full... looking forward to the day when the real decisions in America are made by working class families gathered around the kitchen table... new postings daily...Yours in the struggle...Alan L. Maki

Canadian workers and their New Democratic Party are blazing the path of independence from the big-business controlled political parties. Manitoba will be having elections in the fall. Workers here in the United States should be paying attention to Canadian politics as there is a lot to learn. Ask your union to link its websites to the Canadian Labour Congress, New Democratic Party and Manitoba NDP.

Also, I would encourage you to paste this into your own personal blogs, web sites and FaceBook and other social netwoking sites.

Here are the links:

Canadian Labour Congress---

http://www.canadianlabour.ca/home

New Democratic Party---

Manitoba NDP---

Also, check out Howard Pawley's new book---

"A Life in Politics, Keep True" available through:

http://msupress.msu.edu/bookTemplate.php?bookID=4250

Check out my blog:

http://thepodunkblog.blogspot.com/

This blog is proud to be a part of the ever growing and expanding People Before Profit network.

Due to recent budget cuts and the cost of electricity, gas and oil, as well as current market conditions and the continued decline of the economy, The Light at the End of the Tunnel has been turned off.

We apologize for the inconvenience.

| |

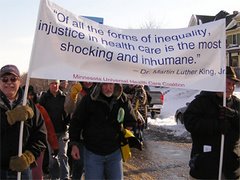

The United States has 800 military bases on foreign soil... What we need--- instead--- is 800 public health care centers spread out across the United States where people can universally access, for free, all their health care needs from pre-natal care, to general health care to eye, dental and mental care right through to burial.

Instead of moving in this progressive direction, President Barack Obama and the United States Congress are moving in a most reactionary direction towards establishing military bases in outer space as they seek to insure the profits of both the merchants of death and destruction and the profit-driven health care industries... talk about skewed priorities and your wacky ideas which will execerbate the problems surrounding the failing capitalist economy, and ideas devoid of common sense.

In addition to these 800 U.S. military bases on foreign soil, Barack Obama and the United States Congress continue funding--- with our tax-dollars--- the Israeli killing machine to the tune of tens of billions of dollars. Where is the "change?"

This is the change Americans want, and the change we need:

A network of 800 public health care centers spread out across the United States would create over four-million good-paying, decent jobs--- talk about your "economic stimulus" package!

We would be redistributing the wealth as we are planting the seeds of socialism while helping to eradicate poverty by keeping people healthy and getting them well when sick.

Think about this kind of solution in relation to what Barack Obama, the U.S. Congress and the Wall Street bankers and coupon clippers are offering the American people, and the peoples of the world... just what is the reason for bailing out the banks and AIG and maintaining more than 800 expensive U.S. military bases of foreign soil?

The Mt. Carmel Clinic in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada offers us a glimpse at what militarization and wars continue to rob us of.

The problems created by Wall Street will not be solved as long as the military-financial-industrial complex is allowed to squander human and natural resources on militarism and wars... we might just as well be dumping these resources out into the ocean... at least no one would die in wars.

These merchants of death and destruction must be stopped if humanity is to survive in a livable world.

The time has come to talk about working class Marxist politics and the economics of livelihood... capitalism has failed humanity miserably and left us a real mess to clean up.

Capitalism is on the skids to oblivion and unless we take a "left turn" we will continue down this road to perdition.

Something for working people to think about and discuss around the dinner table... the capitalist sooth-Sayers certainly are not going to broach such solutions to the problems of working people as they hide behind the skirt of Rosy Scenario as this global capitalist economic depression intensifies while wars rage on.

The times and conditions call for "building a new era of justice and peace;" this is one step in that direction; this is the change the American people voted for.

Alan L. Maki

Founder,

Frank Marshall Davis Roundtable for Change

Everybody knows the boat is leaking. Everybody knows the captain lied.... Everybody knows the plague is coming. Everybody knows it’s moving fast. Everybody knows ...

— Leonard Cohen

Chorus:

This land is your land, this land is my land

From California, to the New York Island

From the redwood forest, to the gulf stream waters

This land was made for you and me

As I was walking a ribbon of highway

I saw above me an endless skyway

I saw below me a golden valley

This land was made for you and me

Chorus

I've roamed and rambled and I've followed my footsteps

To the sparkling sands of her diamond deserts

And all around me a voice was sounding

This land was made for you and me

Chorus

The sun comes shining as I was strolling

The wheat fields waving and the dust clouds rolling

The fog was lifting a voice come chanting

This land was made for you and me

Chorus

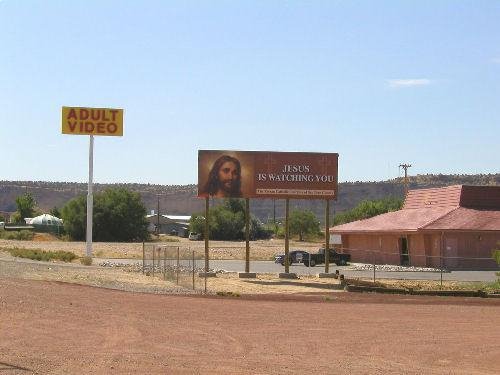

As I was walkin' - I saw a sign there

And that sign said - no tress passin'

But on the other side .... it didn't say nothin!

Now that side was made for you and me!

Chorus

In the squares of the city - In the shadow of the steeple

Near the relief office - I see my people

And some are grumblin' and some are wonderin'

If this land's still made for you and me.

Chorus (2x)

He could get it fixed on Wall St.

Write A Letter To The Editor--- a very effective way to influence public opinion.

By: Alan L. Maki

Letters to the Editor are an effective way of speaking to a large group of people, and often getting the attention of elected officials; but, most important is that elected public officials understand that through a Letter to the Editor you are speaking directly to your friends, neighbors and fellow workers in the proverbial public square and these politicians will understand that their own positions are being publicly challenged and people are beginning to “think outside the box” which often leads to movement building.

First, you should pick an issue that you feel strongly about and you are familiar with; citing your own personal experiences with unemployment and poverty or with war makes for a very strong Letter to the Editor.

One important thing to remember is that newspapers like to publish letters that have a local tone; so your letter should address how the issue is pertinent to people in your area.

Also, it is best to always refer to an article that was published in the newspaper you are submitting your letter to. State that you are opposing or supporting the views in the article or editorial. Give the date and page of publication you are referencing.

If you need the address for your local paper, check out this site which has links to newspapers all over Minnesota: http://www.mnnews.com/

Remember to show your published Letter to the Editor to everyone you know; encourage them to write, too.

If you and a couple friends get Letters published you can photo-copy them and use it as a leaflet.

One effective way to use Letters to the Editor to build movements is to write a Letter and then get friends to follow up with Letters of their own on different aspects of the issue.

Remember to stick to the newspaper's guidelines as to limitation on words, etc. that the newspaper establishes.

* If your Letter doesn't get published, call the Editor and ask for the reason your letter wasn't published. Often the Editor will suggest “corrections” that you can make and then you can resubmit the Letter for publication consideration. Also, don't waste a Letter to the Editor; submit it to another paper if one doesn't publish it.

There are some important working class issues many Editors of corporate newspapers will not publish unless pressured to do so. If this happens then take the opportunity to publish your Letter as a leaflet with a big, bold headline like this: The Duluth News-Tribune refused to publish this--- why? What is happening to democracy in our community?

If you are working on an issue or problem, gather together a few people and have a Letter to the Editor writing party at your home, in a union hall, community center, library, church or park. Libraries are good places to have such a party because you have many resources available.

Provided courtesy of:

The Podunk Blog http://thepodunkblog.blogspot.com/

A blog for working class activists.

Alan L. Maki, publisher

58891 County Road 13

Warroad, Minnesota 56763

Phone: 218-386-2432 Cell Phone: 651-587-5541 E-mail: amaki000@centurytel.net

An example of some well-written Letters to the Editor which were published:

http://nativeamericanindianlaborunion12.blogspot.com/2009/08/letter-to-editor.html

This was rejected by the Editor as a Letter to the Editor because of its length but the Editor then agreed to publish it as an Op-Ed piece: http://nativeamericanindianlaborunion12.blogspot.com/2009/08/grand-forks-herald-op-ed-piece.html

A good writing guide: “Elements of Style” by W. Strunk & E. B. White; free on-line: http://faculty.washington.edu/heagerty/Courses/b572/public/StrunkWhite.pdf

Each of us is like one little snowflake; we don't amount to much... but watch out for a Minnesota blizzard!

Reader's view: Money should go to health care and jobs, not wars

Listening to Democrats making excuses for Obama has been sickening. People voted for peace and got more war. People voted for health-care reform and got a health insurance industry bailout and profit maximization act. The Democrats scream, “Jobs, jobs, jobs!” and we get more unemployment and poverty-wage jobs.

Common sense tells us to end these dirty wars and use the money to pay for a world-class, socialized, health-care system, providing free health care for all, which would create as many as 10 million new jobs with the enforcement of affirmative action.

Every single delegate to the Minnesota DFL State Convention in Duluth should have to pass through a gauntlet of warriors for peace and social justice, insisting on the change they voted for. If we can’t get peace with social justice out of the Democratic Party, we are going to have to look elsewhere —possibly start a new political party.

Alan L. Maki

Warroad, Minnesota.

The writer is a delegate to the 2010 Minnesota DFL State Convention in Duluth.

[This recipe, from the New York Times, really is simple and produces a crusty crust and soft interior. It uses the bare minimum of ingredients, and no kneading, and works fine with either free-standing or pan loaves. Next time I may enhance it with sun-dried tomatoes, or Kalamata olives, or onions.]

A. 9 large potatoes

B. 1 16 oz container sour cream

C. 2 cans cheddar cheese soup

D. 1/2 cup melted butter

E. 2 tsp salt

F. pepper to taste

G. 1 pint half and half or regular milk or evaporated

H. onion – optional

I. 12 oz package of mild shredded cheddar cheese

Seven easy steps…

1. Cut uncooked potatoes in thin slices

2. Spray 9x13 pan with oil spray

3. Layer cut potatoes in oiled pan

4. Mix above ingredients together

5. Pour ingredients on top of potatoes

6. Bake at 350 degrees for one hour or until potatoes are soft and done

7. Ten minutes before taking out of oven add shredded cheese

Green Tomato Preserves

8 lbs. green tomatoes, cut up

4 lbs. sugar

1 quart vinegar (white)

1 tbsp powdered cloves

1 tbsp cinnamon

1 tbsp salt

Boil slowly and stir frequently till thick. Can in sterile jars.

Red Pepper Jelly

7 sweet red peppers

2 sweet yellow peppers (optional)

5 hot peppers

1½ cups vinegar

1½ cups apple juice

1 package powdered pectin

½ teaspoon salt

5 cups sugar

Wash peppers and remove stems and seeds. Cut up. Puree peppers and vinegar. Stir in apple juice. Refrigerate overnight.

Strain mixture through cheesecloth. Measure 4 cups juice. Combine juice, pectin, and salt in a saucepot. Boil over high heat, stirring constantly. Add sugar, stirring until dissolved. Boil 1 minute more, stirring. Remove from heat, skim foam (if any).

Ladle hot jelly into hot, sterilized jars. Process 5 minutes in a boiling water canner.

Tomato juice

Cook the following for half an hour:

Heirloom tomatoes, mixed varieties and colors

Fresh herbs (basil, Italian parsley, oregano, thyme)

celery, chopped

carrots, chopped

onions, chopped

garlic, cut up

hot and sweet peppers, cut up

lemon juice

salt, pepper

Any system you contrive without us

will be brought down

We warned you before

and nothing that you built has stood

Hear it as you lean over your blueprint

Hear it as you roll up your sleeve

Hear it once again

Any system you contrive without us

will be brought down

You have your drugs

You have your guns

You have your Pyramids your Pentagons

With all your grass and bullets

you cannot hunt us any more

All that we disclose of ourselves forever

is this warning

Nothing that you built has stood

Any system you contrive without us

will be brought down

1 LB Chicken Breasts Fillets,Cubed

1/3 Cup Herb Vinegar

1/3 Cup Garlic Oil

1 Tablespoon Soy Sauce

1 Teaspoon Crushed Fresh Ginger

1 Tablespoon Sherry

24 Button Mushrooms

24 Cherry Tomatoes

1 Green Pepper,Cubed

1 Red Pepper,Cubed

12 Pickling Onions

2 Tablespoon Chopped Chives

8 Nasturtium Flowers,Chopped

Pickled Nasturtium Seeds,Chopped

1/4 Cup Plain Yogurt

Salt and Pepper to Taste

Nasturtium Leaves

Marinate the chicken in a glass dish overnight in the combined vinegar,garlic oil,soy sauce,ginger and sherry.

Drain the chicken and reserve the marinade.

Thread the chicken and vegetables alternately onto 8 skewers.

Grill or barbecue the kebabs,brushing with the reserved marinade,until cooked through.

Combine the chives,nasturtium flowers and seeds then mix the plain yogurt and salt and pepper to make a dressing.

Remove the kebabs from the skewers and serve on the nasturtium leaves.

Top with the dressing.then roll up and eat.

Serves 4......ENJOY!

| BREAD AND BUTTER PICKLES (REFRIGERATOR) | |

10 med. cucumbers 3 med. sweet onions 4 c. white vinegar 3 c. sugar 1/2 c. Kosher salt 2 1/2 tsp. tumeric 1 tsp. mustard seed Wash cucumbers; slice them, put unpeeled cucumbers into a gallon glass jar. Put onion slices every few layers, Mix vinegar, sugar, salt and spices together and pour over cucumbers. Let stand in refrigerator for 24 hours before eating. Stir once in awhile. Will keep indefinitely in refrigerator. | |

• 2 1/2 tbsp fresh cake yeast or 1 pkg dry yeast

• 1 cup lukewarm water

• Pinch of sugar

• 1 tsp salt

• 3-3 1/2 cups unbleached white flour

Warm a medium mixing bowl by swirling some hot water in it. Drain. Place the yeast in the bowl, and pour on the warm water. Stir in the sugar, mix with a fork, and allow to stand until the yeast has dissolved and starts to foam, 5-10 minutes. Use a wooden spoon to mix in the salt and about one-third of the flour. Mix in another third of the flour, stirring with the spoon until the dough forms a mass and begins to pull away from the sides of the bowl. Sprinkle some of the remaining flour onto a smooth work surface. Remove the dough from the bowl and begin to knead it, working in the remaining flour a little at a time. Knead for 8-10 minutes. By the end the dough should be elastic and smooth. Form it into a ball. Lightly oil a mixing bowl. Place the dough in the bowl. Stretch a moistened and wrung-out dish towel across the top of the bowl, and leave it to stand in a warm place until the dough has doubled in volume, about 40-50 minutes or more, depending on the type of yeast you used. (If you do not have a warm enough place, turn the oven on to medium heat for 10 minutes before you knead the dough. Turn it off. Place the bowl with the dough in it in the turned off oven with the door closed and let it rise there.) To test whether the dough has risen enough, poke two fingers into the dough. If the indentions remain, the dough is ready. Punch the dough down with your fist to release the air. Knead for 1-2 minutes. Divide dough into smaller balls.

Roll to desired thickness, top with desired ingredients, and bake at 475° until crust is crispy and golden (about 10 minutes).

The trick is to ALWAYS use a pizza stone to bake on, it is not nearly as good and crispy if you don’t...