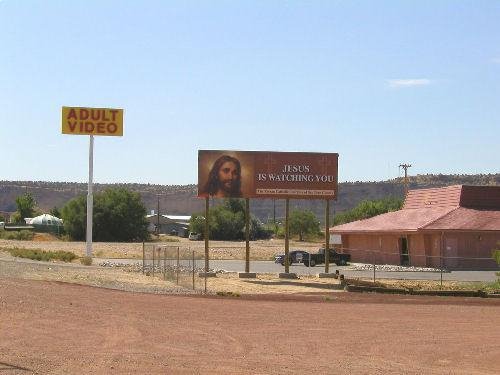

Water, water, everywhere? Just bottle it and turn water into another commodity for big-business to profit from using cheap labor?

Or...

...protect our most precious resource from the clutches of the corporate profiteers?

I would encourage everyone to join in this important discussion taking place on the Great Lakes Town Hall web site. If this isn’t an issue we should be able to expect every single candidate from township board to the presidency to provide their views on, I don’t know what issue would be… On this issue of defending our water, progressives should be able to find common unity like in no other issue… after all, we are talking about our very lives… water is life. If we can’t find common ground in defending our water, what can we find common ground to work on?

Please circulate and distribute this e-mail widely to all your lists; post on blogs and website; print and distribute to friends and neighbors; bring it to school for discussion.

I will continue adding the ongoing discussion so keep checking back on this issue... it will be listed on the side.

Introduction:

The Great Lakes and Humankind

Gary Wilson (Chicago, Illinois)

At the highest levels, our society operates based on policies – those mission statement type declarations that determine a course of action. Our constitution could be looked at as a policy statement.

How we manage our natural resources also needs guiding policies, including for this region’s abundance of water.

We are fortunate to have in our circle of Great Lakes experts, Dave Dempsey -- author, conservationist, and policy advisor.

Dempsey recently gave a policy speech on our role as stewards of 20% of the Earth’s fresh surface water, the Great Lakes. The speech was timely as we are now debating and considering a document, the Compact, that may guide our water policy for decades, if not centuries.

The venue was Michigan State University’s Alumnus Lecture Series and the presentation was titled: Stewardship of Water in the 21st Century: Our Responsibility as Great Lakes Basin Inhabitants.

This was a substantive talk that should challenge us to think beyond our normally provincial viewpoints. Whatever I could write about the speech wouldn’t do it justice. I’ll instead give you excerpts designed to encourage you to read further. You won’t be disappointed.

But I ask one favor. Reflect on the speech for a few days before coming to conclusions. Dempsey’s comments deserve more than a summary judgment.

Here are some highlights.

On consideration for the people of the world who do not live with the abundance of fresh water that we in the Great Lakes region have.

“I hope my remarks today will be a small curative…..helping you and me alike stretch our thinking and expand our empathy to take into account people we will never know...These are people we need to keep in mind as we in the Great Lakes Basin define our stewardship of nearly one-fifth of the world’s available surface fresh water.”

On the overall scarcity of water in the world.

...”I think there are perhaps near-imminent circumstances under which the U.S. and Canada and their peoples will be asked to share water with human sufferers in crisis. Would we really say “no” to hundreds of thousands of whose lives were at risk?

On this region’s permissiveness towards private corporations who are allowed to sell our water for profit, while many suffer without water.

“I would ask you to consider, then, why it might be unthinkable to give away Great Lakes water, so essential to life, to the distressed – but it’s fine to sell water to those who are not distressed.”

Dempsey’s speech should be required reading for every legislator and policy maker in the Great Lakes Basin.

It’s that important

gw

You can find the entire text below.

Editor’s note – Dave Dempsey is a co-editor of the Great Lakes Town Hall

02:32 pm 04/27/2008

Stewardship of Water – the Oil of the 21st Century:

Our Responsibility as Great Lakes Basin Inhabitants

By David Dempsey

Dave Dempsey is a co-editor of the Great Lakes Town Hall

http://www.greatlakestownhall.org/index.php

The venue for this speech was Michigan State University’s Alumnus Lecture Series and the presentation was titled: Stewardship of Water in the 21st Century: Our Responsibility as Great Lakes Basin Inhabitants.

You know, probably one of the hardest things for any one of my background to do – anyone born Caucasian and thus privileged, middle-class and comfortable in the mid-20th Century into the most affluent society ever -- anyone raised to believe that the U.S. was the hope of all humankind, anyone confident that time was a linear march of progress – one of the hardest things for us to do has been to visualize the world from a non-American perspective. To think beyond what I was raised to believe was the inherent greatness of America.

Sure, my earliest memory of public life as a child is the assassination of John F. Kennedy, and the murders of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy are also vivid, and cast some doubt on the legends which I’d been spoon-fed. The Vietnam War was a blot on our nobility. And when the Watergate scandal toppled a corrupt President, I had even more cause to wonder.

Come to think of it, how did I live through such dark history and still think America was the last best hope on Earth?

I suppose part of it was our technological prowess – dramatized by the successful U.S. moon landing in 1969, when I was 12.

I suppose part of it was the sense that despite the loss of Dr. King, we were beginning to make a run for the far-off promise of a truly just, fair and civil society.

I suppose part of it was the idealism of my own father, who having survived infantry combat in World War II returned home to build a better society and taught me that public service was a noble calling. He spent his best and most productive years in that service.

But I am pretty sure part of it was the singular, secular faith of Americans at that time – that we were smart, hard-working, and downright good-intentioned. We loved our society so much we wanted the whole world to join us in it! We made mistakes, but we were still the world’s envy.

Contrast that with one of the memories that persists in my mind from a graduate-level class that I took eight or nine years ago. As was typical then, about half the students were from what we call the developed world, and half from the developing world. During one of the class discussions, a student from a Latin American nation shamed us into silence with a litany of the destructive foreign policies the U.S. had pursued in that nation in order to protect major American corporations.

In the effort to keep that nation ‘safe for democracy,’ the U.S. had helped overthrow a lawful government, sided with the corporations against indigenous peoples, and looked the other way at a surge of violence that caused heavy casualties across the rural landscape. Summing up his nation’s experience, this student visiting America looked at us somberly and said, “You Americans are nice people, but you don’t have a nice government.”

I recall this episode not to make the point that America is an imperfect nation – we all know that – or to condemn any particular foreign policy. In the context of what I agreed to talk to you about today, I recall it to remind us that we in the U.S. are a uniquely self-focused people. It’s not just that our government sometimes commits acts in our name that are uncivilized, and undemocratic – it’s also that many of us are ignorant about these acts, and the toll they take in human lives and hope in faraway lands.

I hope my remarks today will be a small curative for that, helping you and me alike stretch our thinking and expand our empathy to take into account people we will never know, but who are every bit as human and complicated and deserving and damnable as we are. These are the people we need to keep in mind as we in the Great Lakes Basin define our stewardship of nearly one-fifth of the world’s available surface fresh water.

That’s right – about 18% of the world’s surface fresh water – but only about 0.5% of the world’s population. We may have only about 1/200th of the globe’s people, but we have close to one-fifth of humankind’s responsibility for freshwater.

Enough fresh water to pour out over the 48 contiguous states and create a continent-wide swimming pool 9.5 feet deep.

Enough fresh water coastline to reach 44% of the circumference of the earth at the equator.

Enough fresh water to fill up 6 quadrillion gallon containers.

What do all these numbers really mean?

I suggest they mean that as we consider the fate of these Great Lakes, we must widen our circle of consideration beyond the eight Great Lakes states and two Canadian Great Lakes provinces…beyond the U.S. and Canada…beyond the Native American tribes and First Nations peoples who first cherished and drew sustenance from the Lakes.

We must widen our circle of consideration beyond the limits of nationalism, binationalism and even North Americanism to include all of humanity. What responsibility do we have as Great Lakes stewards to all of humanity? How do we exercise that responsibility with care? And as an American, I want to know, how can we avoid in the area of fresh water policy the mistake of self-involvement that has enabled our government to commit acts in our name that many of us would never dare undertake as individuals?

Unfortunately, for most of the quarter century that I’ve been tracking the Great Lakes water question, self-involvement has been the rule. No matter how you define “self.” State, regional or national self.

In the early and mid 1980s Michigan had unemployment that reached 17% and the sardonic expression was coined, “Last one out of Michigan turn off the lights.” As Sunbelt states drained our jobs, we feared they would drain our water, too. And so Michigan said “no,” and we took the lead in fashioning the first regional (and relatively weak) agreement to protect the Great Lakes. It was the right thing to do – but it was motivated as much by fear as enlightenment, or love of the lakes.

In the late 1990s, when a Canadian company proposed shipping 50 tankers of Lake Superior water per year to high-end markets in Asia, we reacted viscerally again. The answer again was “no,” and the Great Lakes region began the seven-year process that led to the water compact and agreement that are now being considered in this region. It was the right thing to do – but it was motivated as much by xenophobia as by enlightenment, or love of the lakes.

And where are we today when it comes to considering the husbandry of the lakes?

I’m afraid we’re still mostly talking about whether the Sunbelt, or corporations, or wealthy foreign markets will get our water. And we’re still debating whether our laws or policies or practices will meet that goal. Those are legitimate issues, but they overlook the biggest consideration of all.

It’s called water scarcity, and it’s coming to a continent near you…no matter what continent you live on.

You’ve probably heard the news. By the year 2025, it was predicted late in the 20th Century, one in three human beings will be affected by water scarcity. That alarmist prediction turned out to be wrong.

At a 2006 conference, the International Water Management Institute reported that a comprehensive assessment, carried out by 700 experts from around the world over five years, indicated that one third of the world's population was then already living in places where water is either over-used – leading to falling groundwater levels and drying rivers – or couldn’t be accessed due to the absence of the appropriate infrastructure.

As one author of the assessment said, “[W]hile a third of the world population faces water scarcity, it is not because there is not enough water to go round, but because of choices people make…People and their governments will face some tough decisions on how to allocate and manage water. Not all situations are going to be a win-win for the parties involved, and in most cases there are winners and losers. If you don’t consciously debate and make tough choices, more people, especially the poor, and the environment will continue to pay the price.”

What does that mean for our conversation today about the Great Lakes? A lot of things, obviously. But I’d like to point to a few words in the pending Great Lakes compact that have a lot to do with global water scarcity. And practically nobody is talking about them.

Those words are: “To use in a non-commercial project on a short-term basis for firefighting, humanitarian, or emergency response purposes.”

For those of you keeping score, they are found in section 4.13, “Exemptions,” page 21 of the Great Lakes Compact. The half-sentence defines exemptions to the compact’s ban on water exports.

In other words – without any definition – the states are saying it is permissible to take water out of the Lakes “on a short-term basis” for “humanitarian or emergency response purposes” that are “non-commercial.”

Think about that a moment.

Too often in the last 25 years the rhetorical skirmishes over the future “sharing” of the Great Lakes have played out in public as Sunbelt greed versus Great Lakes hoarding. As a Michigan-born man I understand and share the instinctive local opposition to water exports from the Great Lakes to anywhere on earth, and the resulting perception of outsiders that a colony of human water hogs inhabits the region. But no one has really asked the people of Michigan or any of their Great Lakes neighbors whether they are willing to relinquish some basin water to save human lives.

The closest we’ve come to this point is not very close. In 2005, when Katrina walloped New Orleans and the adjoining Gulf shore, the Great Lakes water commercialization industry smelled an opportunity. We all watched as helpless thousands of our fellow citizens lived in bestial conditions for days. In the late summer heat, elderly and vulnerable refugees slowly died awaiting medical attention, air-conditioning, food—and water. Major water bottlers were happy to help, shipping planeloads and truckloads of water to address the suffering. Here in Michigan, Governor Granholm temporarily lifted a state ban on new bottled water exports in a symbolic gesture of humanity.

But as dramatic as the Katrina catastrophe and the governor’s directive was, it was also unique in the long-running fight over Great Lakes water exports. At no other time since the fight began in the 1980s have American citizens on such a mass scale been in need of emergency drinking water. One can only hope the disaster does not repeat itself in the future.

The unasked and unanswered question after Katrina is whether

Michigan or any of the Great Lakes states would have been as quick to relax a Great Lakes export restriction for sufferers in South America, Africa, or Asia. And, barring further federal government malfeasance and incompetence on the scale seen after Hurricane Katrina, this is likely the next scenario in which Great Lakes water may become a humanitarian resource.

Water scarcity abroad—threatening human survival—is likely to be a persistent theme of the twenty-first century. And such scarcity could last much longer than the post-Katrina weeks in which New Orleans residents languished. How will we respond? How much if any will we share? How long will it last? Who will decide?

We might want to start thinking about those questions. In fact, it’s our responsibility to do so.

Did any of you have a chance to read The Price of Loyalty by David

Suskind? It’s one of the earliest exposes of the inner workings of the Bush II Administration and to me, still one of the most powerful and heartbreaking. It’s about the two-year stint of former Alcoa CEO Paul O’Neill as U.S. Secretary of the Treasury.

Secretary O'Neill took an extraordinary tour of Africa in May 2002. Accompanied by international rock star Bono, he spent over a week visiting villages with no safe water and AIDS hospitals with woefully inadequate care.

Conservative Republican Paul O’Neill returned from his trip determined that the United States should do something real to help Africans, particularly in the areas of clean water and AIDS. He was confident that with concerted American assistance, there might be dramatic improvements in providing clean well water with a relatively small amount of money.

O'Neill recognized that force alone will never suffice to eliminate all the sources of antagonism towards the United States and terrorism directed at our nation.

He said, “We needed a nonmilitary side to our foreign policy, where the U.S. could start treating much of the beleaguered developing world – the source of so many of the threats to our security–in a way that showed we valued and respected them. We needed to do some things that showed measurable good – that the U.S. could be a force for good in people’s lives.”

He didn’t get much support from his peers in the Cabinet.

But he persisted, and sought a personal meeting with the President. In one of the most defining scenes of the post 9/11-era, O’Neill asked the president to fund a $25 million demonstration project to provide clean water in Ghana. The President did not seem to comprehend why O’Neill was taking up his time on this. O’Neill left the office without an answer. Before long he was out of the Bush Administration. The idea went with him.

As commentator Thad Williamson said, “This is not simply another story of the powerful and comfortable turning a deaf ear to the cries of the sick and poor, or a story of half-hearted excuses being used to rationalize inaction. The rejection of O'Neill's initiative – paralleled by a headlong rush into military confrontation with Iraq – also represented a major strategic decision by the Bush White House.”

I bring up the point today because I think there are perhaps near-imminent circumstances under which the U.S. and Canada and their peoples will be asked to share water with human sufferers in crisis. Would we really say “no” if hundreds of thousands of lives were at risk? What would it take to get us to say “yes”?

I suggest it might take an initiative like what Bono and Secretary O’Neill envisioned – short-term relief coupled with the development and conservation of water resources in the home nations where scarcity exists. In that unique American combination of selflessness and self-interest, we could save lives, export our water technology abroad and make a profit, and promote water self-sufficiency in some developing nations. We might then also restore to a mild degree our tarnished image abroad.

But you won’t find any more than a passing reference to this scenario -- I think the most likely mid-term scenario of out-of-region water demand upon the Great Lakes – beyond those few cryptic words in the compact. It’s time that we corrected that.

Now there may be some who strongly disagree with my suggestion that we entertain the idea of water sharing with the distressed and dying. And there are many who think selling and exporting Great Lakes water in bottles is no different from selling and exporting juice made with Great Lakes water in bottles. In other words, you don’t see the big deal about the so-called bottled water exemption in the Great Lakes compact.

How many of you feel that way?

I would ask you, then, to consider why it might be unthinkable to give away Great Lakes water, so essential to life, to the distressed – but it’s fine to sell water to those who are not distressed.

Or even more importantly – how it can be ecologically unsound to ship 300 million gallons a year of water out of the Great Lakes in tanker trucks or vessels – but perfectly permissible to ship 300 million gallons a year of water out of the Great Lakes in 16-ounce plastic bottles? That’s the logic or illogic behind the Great Lakes compact. And I’m worried that it betrays a fatal gap in our thinking and feeling.

We have begun, I believe, to allow the Great Lakes to be converted to a product. And this we must never do.

In treating water as the common heritage of mankind, we have plenty of law and plenty of poetry – some of it in court rulings – that stands behind us.

In a landmark public trust case, Collins v. Gerhardt, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled in 1926 that the rights of citizens to fish, swim, boat and enjoy public trust waters “are protected by a high, solemn and perpetual trust, which it is the duty of the state to forever maintain.”

Going back even farther, the U.S. Supreme Court held in 1892 that “the basic common law principle of the public trust doctrine is that the trust can never be surrendered, alienated, or abrogated. It seems to be a rule, beyond question, that the rights of the public are impressed upon all navigable waters, and other natural resources which achieve a like public importance [emphasis added]. And the state may not, by grant or otherwise, surrender such public right any more than it can abdicate the police power or other essential powers of government.”

This all stems from an ancient Roman code, and an equally venerable human belief, which holds that some natural resources are not ownable – they cannot in the end be private. They are the property of all humanity. It is called the public trust doctrine. And as the Michigan Supreme Court said in 1926, protecting this public trust is a high…solemn…and perpetual duty.

And yet here we are, 82 years later, and our governments are abdicating their police power and they are surrendering the public’s rights in the Great Lakes. For even if you don’t think there’s anything wrong with putting the public’s water into bottles and selling it, don’t you think the public should be asked to decide whether that’s OK? But the public has not yet been asked that question – and large-scale commercial capture and sale of water is now happening in the Great Lakes Basin. Without any open debate, any law authorizing it, or any clear public affirmation that this is consistent with the public trust.

It’s absurd, and it should be stopped. We are giving humanity’s water to private interests, who are selling it at an outrageous profit and benefiting the public almost not at all.

The one thing we must not do as brothers and sisters of humankind is the one thing we have done so far this century – sanctioning the privatization of our water.

Do we really want water to be, literally, the oil of the 21st Century?

Do we really want water to be subject to the same erratic, exploitative control and pricing that petroleum is subject to? Imagine a 20 cent per gallon price rise in one day for water, as I witnessed last week for gasoline at the corner service station.

With water, such a jump wouldn’t be a mere inconvenience – it could kill.

Water is different.

Water has a spiritual value.

Water is life.

And now let us turn to Michigan’s responsibility as steward of the Great Lakes. How can it be that Michigan is one of the laggard states in the nation in promoting water conservation? Michigan, which has more to gain or lose than any other state in the nation from fresh water policy.

Until two years ago, Michigan didn’t even have a statute that regulated the most mammoth water users in the state. If some upstream neighbor – a golf course or a Nestle -- came along and pumped the river running past your property dry, no government agency would come to your aid. Or the river’s aid. You had to hire a lawyer and go to court.

Now Michigan does have such a law, but it’s riddled with holes. It needs to be fixed.

I hope that advocates like the Michigan Environmental Council will be able to persuade the legislature to do the fixing in the right way this year.

But I’m now old enough to realize that environmental laws aren’t enough.

Environmental ethics are also necessary, and in some ways, more powerful. It’s time for Michiganians to develop a water conservation ethic.

I say this as some who has closely studied, and passionately loves this state’s conservation history. Like many in the Western world, and many other states in the U.S., Michigan has been governed by what I call ‘the myth of inexhaustibility.” First the white pine forests…then the fish and game…now the land over which development sprawls. With each of these resources we’ve gone on a binge that has led to enormous public costs later. Because we’ve assumed with each of these resources that no amount of human consumption could possibly deplete them.

Let’s not do that with the Great Lakes. Let’s not assume they’re so vast that Michigan can continue wasting water. It makes no sense politically – why would the other seven Great Lakes states respect our wishes that they not export water if Michigan is treating the same resource as though there’s limitless supplies?

It makes no sense ethically, either.

Think back to our experience with the forests that covered most of the state when European settlement began. In the 1850s, although a large area of Michigan contained marketable stands of species such as oak, maple, beech, cherry, elm, hemlock, cedar and balsam, the early speculators and lumbermen had eyes chiefly for the so-called cork or white pine. Often found on ridges and uplands, these choice trees were the kings of the forest, anywhere from 100 to 300 years old and between 120 and 170 feet tall.

The race was on. By 1870, Michigan was the leading timber producer among the states. The trees fell fast, but the predictions of 500 years of prosperity from the native forest persisted. There was simply too much timber to use up.

But just 30 years later, here’s what one observer said of a trip through northern Michigan: “ In traveling nearly two thousand miles through some forty counties in the lumber regions of the State, I cannot now recall having seen in any one place as much as a single standing acre of white pine in good condition.” Riding from Manistee on the Lake Michigan shore to Saginaw, this observer added, he had seen an almost continuous succession of “abandoned lumber fields, miles upon miles of stumps as far as the eye can see…”

Out of those fields of stumps and slash here and in neighboring states rose murderous fires that burned whole counties and killed hundreds of residents. And out of that ruinous lesson came the modern 4-million-acre state forest system, nurtured by public servants now for 100 years. It’s a treasure for this state, but it was earned the hard way.

As Michiganians, let us not repeat that mistake with our water, and with the Great Lakes. Let us conserve now, and set an example for other states, other peoples, and the future.

As Frank Ettawageshik, Chair of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians memorably said, “One hundred and fifty years ago we had a resource in the Great Lakes region that was considered inexhaustible. It lasted barely two generations. This was the White Pine forest. The White Pine of this century is Water.”

I want to close by talking briefly about what growing up in Michigan, surrounded by fresh water, meant to me.

In our grainy family black-and-white snapshots, whose ends are now curled with age, three young brothers under the age of nine with crew cuts stand squinting and smiling in the shallow water off a Lake Michigan beach. One of the boys – me -- has what would be termed a beer belly in an adult, and is gleefully unconscious of the fact.

Wearing shoulder-strap undershirts and swim trunks, the boys are facing landward for the photographer, their father or mother. Behind them is a tinted gray horizon unbroken by waves or the sight of land. In the snapshots, time has stopped in 1962; like summer, the Great Lakes are eternal.

So we all thought, those of us who grew up among the Great Lakes or visited them as children. They’ve always been here, and they always will be. The Lakes were part of our earliest memories, our inheritance, and our hope.

Only as adults did we acquire the statistics that struggled to express that childhood wonder at Great Lakes water.

But it is the curse of adulthood – and politics – to need numbers to justify what the heart knows: that there are no lakes like the Great Lakes, no place like the Great Lakes, and no fresh water more worth defending than the Great Lakes.

As Dr. David Ehrenfeld of Rutgers University once said, “I am afraid that I don’t see much hope for a civilization so stupid that it demands a quantitative estimate of the value of its own umbilical cord.”

Numbers are the province of politics and economics. Wonder has no dollar value. Eternity cannot be quantified. So it happens that in the equations of public policy – including environmental statutes and cost-benefit analyses – the majesty, lineage and future of the Great Lakes carry no weight. But to me and to you, they are powerfully important.

As I said a few moments ago, there are no lakes like the Great Lakes…

There is no place like the Great Lakes Basin…

And there is no fresh water more worth defending than the Great Lakes.

But for whom are we defending them?

For ourselves?

For our immediate descendants?

Or for all humankind and other living things?

These are the questions worth answering. I hope I’ve successfully encouraged you to consider them.

Thank you.

Question and comments

Alan Maki (Warroad, Minnesota)

This is am important speech which should receive very wide distribution because for once the issue of water is placed in the proper perspective; as is the question of who "owns" the Great Lakes' water.

This speech goes far beyond the self-serving and hypocritical lecture I heard United States Congressman James Oberstar deliver for "Water Day" during the 2008 Freeman Forum at the University of Minnesota.

A question:

The figure of 300 million gallons of water a year is used. Is this the actual figure for how much bottled water is being "used" for bottling at the present time? Do you have the figure beginning the first year of commercial water bottling? Do you have any projections to what this figure will be in the years ahead?

You state: "I suggest it might take an initiative like what Bono and Secretary O’Neill envisioned – short-term relief coupled with the development and conservation of water resources in the home nations where scarcity exists. In that unique American combination of selflessness and self-interest, we could save lives, export our water technology abroad and make a profit, and promote water self-sufficiency in some developing nations. We might then also restore to a mild degree our tarnished image abroad."

I don't think it is correct to say that America has this "combination of selflessness and self-interest." In another part you refer to "people" making decisions.

What does exist is a culture that has been shaped by capitalist greed and the drive for corporate profit where those in the corporate boardrooms are making the decisions that none of us have a say in... this is something quite distinct from the generic term of "people."

In this statement, I think you damage your argument for maintaining water as a public resource not to be commercialized in the Great Lakes Region (which I wholeheartedly and very strongly agree with you on), by stating, "we could save lives, export our water technology abroad and make a profit."

Why must everything always center around making a profit? Why would we suggest it is okay to profit from the misery of a poverty stricken country (which these countries usually are when there is a problem with water supplies), yet take the approach of non-commercialization of Great Lakes water?

Yes, "we" could save lives with a highly developed humanitarian policy on the water question. Yes, we should export our water technology abroad where ever it is needed and requested. But, why must this humanitarian assistance be predicated on "profitability?"

As for your comparisons of water to oil... I do not think that people realize that we are at present paying the exact same price for one pint of water as you do for oil at the Holiday Station/Convenience store.

Who profits? Who pays? Who suffers?

I see a pattern linking these questions; those who profit do so at the expense of those who suffer. Of course, like the people who suffer, the ecosystem suffers as the corporations are the only ones to profit.

I don't see the questions and problems of water being resolved as long as we put up with a social and economic system driven by a quest for maximum profits.

Is there anything which leads you to think that water will be treated any differently from iron ore, oil; or, even human labor under this system?

Here in Minnesota we have three major watersheds to look after... the Great Lakes, Lake of the Woods and Red Lake watersheds and the Lake of the Woods and Red Lake watersheds are fairing even worse than the Great Lakes due to peat mining and iron ore mining; both major contributors to polluting and contaminating all three watersheds.

On top of this you have sulfide mining going into operation in Michigan and Minnesota. Again, threatening all three watersheds. Again, the reason: corporate profits.

Rather than being concerned about the profits in developing water technologies we should finally be truly concerned for a change with creating "jobs, jobs, jobs" in the new "water technologies" that will have to become part of any "greening" of American society and the rest of the world.

Competition for profits has outlived any use it ever had and it is time to start considering a cooperative approach to these problems.

If the competitive drive for profits continues to dominate American society and our thinking we are most likely doomed.

There will always be greater profits in war for the military-financial-industrial complex than what there is in making life better for people.

Einstein explained all of this many years ago in answering the question, "Why Socialism?"

06:07 pm 04/28/2008

Re: The Great Lakes and Humankind

Dave Dempsey (St. Paul, MN)

Alan,

Thanks for your thoughts and questions. You are always thought provoking. I appreciate your interest in the Town Hall.

I'll answer your questions now and think about your comments over the next few days.

The 300 million gallons refers only to the Nestle Corporation's exploitation of Michigan water from two pumping sites. The company has plans to take more there and the figure Basin-wide is substantially bigger. Until the last six months of anti-bottled water publicity, the projections for the future were alarming. They may still be.

You say, "Why must everything always center around making a profit? Why would we suggest it is okay to profit from the misery of a poverty stricken country (which these countries usually are when there is a problem with water supplies), yet take the approach of non-commercialization of Great Lakes water?"

Touche. I am not against profit in any way, shape or form, but I agree that emphasizing profit in the way I did is a form of pandering. I'm more interested in the U.S. showing that it genuinely cares about human beings far away by assisting them, at no profit if required, in dealing with their sustainable water needs.

What alarms me most beside our indifference to faraway water scarcity is the failure of our governments in the Great Lakes Basin to be awake to, or to care about, the imminent danger of commercialization of fresh water. It's happening under our noses and the regional compact going through ratification does little to stop it -- it even creates a loophole expressly designed to permit such commercialization.

11:20 am 04/29/2008

Alan Maki (Warroad, Minnesota)

Thanks for the info on the bottled water.

As I mentioned, I was at the 2008 Freeman Forum which featured Congressman James Oberstar for the main lecture: "Water, Water, Everywhere?"

Notice the question mark.

At the conclusion of Oberstar's lecture, a guy asked him why he wasn't drinking tap water instead of bottled water.

Oberstar arrogantly responded without the least little bit of concern:

"I am sure this water came out of a tap somewhere." He then held up the bottle and took a big swig.

This from a guy who just got done boasting about what a great environmentalist he was.

Just unbelievable.

Water bottling is a big-business not only in Michigan, but Wisconsin and Minnesota, too.

You have probably noticed in many places it is hard to find a drinking fountain any more... everyone wants to sell water to you.

I met with a group of people from White Cloud, Michigan who fought Nestle Corporation. It is really hard for people to fight off these corporations when the government always sides with the corporations.

I think the fight to protect water from corporate domination of this important resource could be a very key unifying factor in getting people to coalesce to begin electing politicians who are not controlled by the corporations.

In spite of a few differences, I think your speech should receive the widest circulation possible. It is the best speech I have read by an environmentalist to date. Hopefully you are sending it to all the environmental organizations.

I sent it to Carl Pope at the Sierra Club and several unions and community organizations.

I don't mean to put all the work on you, but I think if you have the funds, every single state, federal and the provincial politicians should get copies of your speech by snail mail with a cover letter from you enclosed.

You might even ask others to sign on to it kind of "endorsers" of the direction we want to see this issue around water go.

You might even consider something like a "petition" or "an open letter" signed by a bunch of people who say they support the views you express.

People are bound to have some differences with some of the views you express in this speech; but, I think you are going to find the overwhelming majority of the people are going to be very supportive in opposing the commercialization of "our" water as you have articulated here.

11:53 am 04/29/2008

Neoliberal economics and water

Alan Maki (Warroad, Minnesota)

I was asked by William Willers, one of the founders of Superior Wilderness Action Network and a long time environmentalist from Wisconsin to post and circulate this for him as part of our discussion on water. William Willers is Professor Emeritus of Biology, University of Wisconsin at Oshkosh.

Note to readers: This response was a result of an e-mailing I sent out which I later posted to my blog because of the tremendous response I received.

My blog is: http://thepodunkblog.blogspot.com/

-----Original Message-----

From: William Willers [mailto:willers@charter.net'>

Sent: Wednesday, April 30, 2008 10:30 PM

To: Alan L. Maki

Subject: Fwd: Discussion continues... Water, water, everywhere? Just bottle it and turn water into another commodity for big-business to profit from using cheap labor? Or...

Alan: I hope this is not offensive to your beliefs, or to anyone's. I sent it out to get feedback, because I'd like to get a feel for opinions on this issue. I don't know how large your email list is, but if there is a discussion going on I'd appreciate you putting it out to see what reactions it might bring. Bill

[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[[

Begin forwarded message:

From: William Willers

Date: April 29, 2008 4:00:28 PM CDT

To: Alan Maki

Subject: Re: Discussion continues... Water, water, everywhere? Just bottle it and turn water into another commodity for big-business to profit from using cheap labor? Or...

The coming water shortage in the U.S. and elsewhere has been known for many years. In the U.S., Marc Reisner's "Cadillac Desert", published in 1986, invoked history and all that is known of geology and water use to warn society. It was ignored, of course, as desert cities - Phoenix, Tucson, Los Vegas, etc. - went full speed ahead with cancerous growth and libertarian "freedom" and the religion of property rights above all, even as water tables were dropping and rivers being tapped out. The apparent attitude has been "There's money to be made, and sure, we can arm-twist the Great Lakes people when, some day, our actions have caused a crash." Yea free market!

The question becomes one of "When does a person - or a society - have to face the consequences of its decisions and actions?" By extension, "What is the obligation of the Great Lakes to bail out regions or countries whose "leaders" have, with eyes wide open, put themselves and their communities into an entirely predictable situation?"

The Great Lakes Basin is the center - the freshwater "heart", if you will - of North America. It's not that it HAS water, it's that it IS water and ABOUT water. Do take note that even now, with lake levels down, "experts" have no definitive answer as to why. But hell, if you're a Chicago-School, neoliberal economist, it makes all the sense in the world to pipe water to New Mexico, or bottle it and sell it to yuppies, or ship it out of the Basin in tankers to other parts of the Globe, if the "free market" says it's economically feasible.

Sorry, but if nature has taught anything, it's that it has a reservoir of unintended consequences for "experts" who thought they knew what they were doing. And it doesn't matter if shipping water out of the Basin is done with profit as a motive or as humanitarian gesture. I don't know who Dempsey is, and I wouldn't want to disparage someone's honest efforts, but in reading his appeal to my humanitarian sensibilities, I felt I was being set up.

If it is an obligation of Great Lakes people to deal with the water issues of poor nations (even as their populations continue to grow at an absolutely insane rate), it would be most effective, not to mention protective of the Basin Ecosystem, to work for population control in those countries and for improvement THERE of water resources, whatever that might mean in terms of creation of wells or education or water purification plants. One's first obligation is protection of one's home.

09:26 am 05/01/2008

Alan L. Maki

58891 County Road 13

Warroad, Minnesota 56763

Phone: 218-386-2432

Cell phone: 651-587-5541

E-mail: amaki000@centurytel.net

Check out my blog:

Thoughts From Podunk

http://thepodunkblog.blogspot.com/