Aboriginal children were deliberately starved in the 1940s and ’50s by government researchers in the name of science.

Milk rations were halved for years at residential schools across the country.

Essential vitamins were kept from people who needed them.

Dental services were withheld because gum health was a measuring tool for scientists and dental care would distort research.

For over a decade,

aboriginal children and adults were unknowingly subjected to nutritional

experiments by Canadian government bureaucrats.

This disturbing look

into government policy toward aboriginals after World War II comes to

light in recently published historical research.

Photos

View gallery

-

zoom

zoom

When

Canadian researchers went to a number of northern Manitoba reserves in

1942 they found rampant malnourishment. But instead of recommending

increased federal support to improve the health of hundreds of

aboriginals suffering from a collapsing fur trade and already limited

government aid, they decided against it. Nutritionally deprived

aboriginals would be the perfect test subjects, researchers thought.

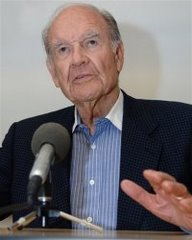

The details come from

Ian Mosby, a post-doctorate at the University of Guelph, whose research

focused on one of the most horrific aspects of government policy toward

aboriginals during a time when rules for research on humans were just

being adopted by the scientific community.

Researching the

development of health policy for a different research project, Mosby

uncovered “vague references to studies conducted on ‘Indians’ ” and

began to investigate.

Government documents

eventually revealed a long-standing, government-run experiment that came

to span the entire country and involved at least 1,300 aboriginals,

most of them children.

These experiments

aren’t surprising to Justice Murray Sinclair, chair of the Truth and

Reconciliation Commission. The commission became aware of the

experiments during their collection of documents relating to the

treatment and abuse of native children at residential schools across

Canada from the 1870s to the 1990s.

It’s a disturbing piece of research, he said, and the experiments are entrenched with the racism of the time.

“This discovery, it’s

indicative of the attitude toward aboriginals,” Sinclair said. “They

thought aboriginals shouldn’t be consulted and their consent shouldn’t

be asked for. They looked at it as a right to do what they wanted then.”

In the research paper,

published in May, Mosby wrote, “the experiment seems to have been

driven, at least in part, by the nutrition experts’ desire to test their

theories on a ready-made ‘laboratory’ populated with already

malnourished human experimental subjects.”

Researchers visited

The Pas and Norway House in northern Manitoba in 1942 and found a

demoralized population marked by, in their words, “shiftlessness,

indolence, improvidence and inertia.”

They decided that isolated, dependent, hungry people would be ideal subjects for tests on the effects of different diets.

“In the 1940s, there

were a lot of questions about what are human requirements for vitamins,”

Mosby said. “Malnourished aboriginal people became viewed as possible

means of testing these theories.”

These experiments are

“abhorrent and completely unacceptable,” said Andrea Richer,

spokesperson for Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Minister

Bernard Valcourt.

The first experiment

began in 1942 on 300 Norway House Cree. Of that group, 125 were selected

to receive vitamin supplements, which were withheld from the rest.

At the time,

researchers calculated the local people were living on less than 1,500

calories a day. Normal, healthy adults generally require at least 2,000.

In 1947, plans were

developed for research on about 1,000 hungry aboriginal children in six

residential schools in Port Alberni, B.C., Kenora, Ont., Schubenacadie,

N.S., and Lethbridge, Alta.

One school for two

years deliberately held milk rations to less than half the recommended

amount to get a ‘baseline’ reading for when the allowance was increased.

At another school, children were divided into one group that received

vitamin, iron and iodine supplements and one that didn’t.

One school depressed levels of vitamin B1 to create another baseline before levels were boosted.

And, so that all the results could be properly measured, one school was allowed none of those supplements.

The experiments, repugnant today, would probably have been considered ethically dubious even at the time, said Mosby.

“I think they really

did think they were helping people. Whether they thought they were

helping the people that were actually involved in the studies — that’s a

different question.”