Today, Barack Obama sees, "

glimmers of hope."

Does anyone other than Obama see these "glimmers of hope?"

But,

where's the change?Barack Obama says the housing market is key to economic recovery.

Others say different.

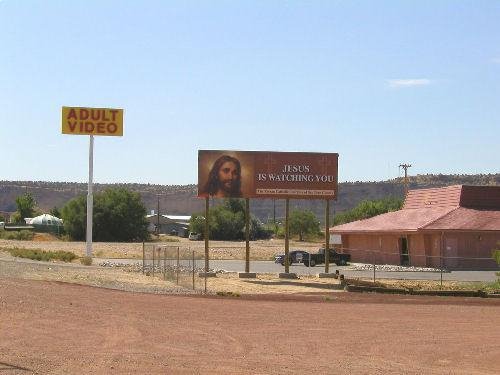

I don't know what they are growing in that White House garden, but Obama must be puffing on something other than ordinary tobacco because he also said today that "home losses" were a big part of the "hardships" Americans are being forced to endure while the media is telling us one out of every nine homes in this country is not occupied and he is doing nothing to stop the foreclosures and evictions when a moratorium for the duration of this depression would be so easy--- especially if he is seeing "glimmers of hope."

These two articles tend to tell us Barack Obama is wrong and hallucinating when he says he sees, "glimmers of hope" and that "the housing market is key to economic recovery."

We really do need to take some time to study this situation because if the President of the United States and his economic advisers don't know what is required for "economic recovery" any more than his military advisers understand what constitutes peace we are in some real deep doo-doo.

Quite frankly, I think we have some way over-paid economists being led around by a President who hides behind the skirt of Rosy Scenario and this definitely does not bode well for us working people.

If the auto and steel industries don't work, the housing problem sure can't be fixed.

What is interesting is that China has become the world's largest steel AND auto producer.

Anyone care to figure out how all of this fits together in a world faced with a global capitalist economic melt-down?

Check out these articles; one from Canada and China, the other from France:

Global steel industry awaits auto turnaroundhttp://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20090412/bs_wl_afp/commoditiesmetalssteelsector

PARIS (AFP) – Steel is on edge and the global industry is cutting back hard, hanging on for either a budget blast from China, new credit for vast Middle Eastern building schemes or resurrection of the US auto industry.

Demand has dwindled and steelmakers, notably the giant of them all, ArcelorMittal, are damping down surplus furnace capacity while waiting for credit to flow, construction cranes to turn and factories to roll.

A decision by ArcelorMittal last week to pursue temporary production cutbacks, slashing European output by more than half from the end of April according to a union source, dramatises the extraordinary ride and role of steel in the last few years.

In just months the global industry has gone from a boom driven largely by China, emerging markets and a property extravaganza in the Middle East to a narrow line between excess capacity and the costs of waiting for recovery.

"Over the past six months, demand for steel has dropped dramatically and, as a result, producers have been cutting production," analysts at Barclays Capital said in a study last week.

In another report, Morgan Stanley predicted "the current demand shock to lead to excess steel capacity."

Consequently, the bank said, steel plants should operate at rates below 75 percent of capacity until 2012.

"The steel market is not very different from base metals as a whole, but steel has reacted more rapidly and dramatically since September," said commodities analyst Perrine Faye of London-based FastMarkets.

She said the future of the steel industry depended on three factors -- the impact of Chinese economic stimulus efforts, a pick-up in the Middle East construction sector and a revival of the once mighty US auto industry.

"Chinese imports and exports are at a standstill. Everyone is waiting for the Chinese stimulus package to see if it will revive demand."

The Chinese government last month announced a four-trillion-yuan (580-billion-dollar) package of measures that it said could contribute 1.5 to 1.9 percent to the country's economic growth.

Industry experts have meanwhile spoken optimistically of China's prospects.

Thomas Albanese, chief executive at steel maker Rio Tinto, said earlier this year that the company foresaw "a short, sharp slowdown in China, with demand rebounding over the course of 2009, as the fundamentals of Chinese economic growth remain sound."

Analysts have said steel inventories are falling in China in anticipation of projects expected to emerge from the country's huge stimulus package.

"It is encouraging that the inventory of steel products, especially long products, which are mostly used in construction projects, have started to fall (since the end of March), likely suggesting that end-demand is gathering momentum," Frank Gong, a Hong Kong-based economist for JPMorgan, wrote in a research note.

On-the-ground evidence suggested that the Chinese industry had been re-stocking in the first two months of the year, followed by a pause in March before major infrastructure projects were expected to start in the second quarter, Gong wrote.

In the Middle East, according to Faye, the big problem is a shortage of credit, notably for real estate developers and builders.

Construction planners had "counted on a higher price for oil and on credit to finance their huge projects."

In addition, demand for such facilities, especially in the Gulf, has died.

"They were hoping that Americans and Europeans would buy apartments. But property prices have collapsed in the Middle East as well."

In the United Arab Emirates more than half the building projects, worth 582 billion dollars or 45 per cent of the total value of the construction sector, have been put on hold, a study by Dubai-based market research group Proleads found in February.

In Dubai, one of the states of the UAE, prices in the real estate sector have slumped by an average of 25 percent from their peak in September after rallying 79 percent in the 18 months to July 2008, according to Morgan Stanley.

Faye said the fate of the steel sector was in addition tied to that of the struggling US auto industry, once a thriving steel market but one in which two of its giant players, General Motors and Chrysler, are staring at bankruptcy.

The two companies are currently limping along thanks to billions of dollars in government aid.

"We are waiting to see if the auto sector in the US will get out of the crisis intact," she said.

http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20090411.wrcover11/BNStory/BusinessChina's runaway steel trainApril 11, 2009 at 12:47 AM EDT

FENGRUN, CHINA and TORONTO — Yu Jianshui fidgets in his big leather chair

as he chain-smokes his way through an interview. Times are tough at the

Tangshan Fengrun Zhengda Iron and Steel Co. Ltd.

With China suffering its sharpest economic slowdown in decades, Mr. Yu, the

firm's general manager, complains that he is getting fewer and fewer orders

for his main product, huge bars of raw steel known as billets. In his 23

years in steel, “this is the worst I've ever seen.”

Yet under the corrugated metal roofs of his steel mill, blast furnaces

still blast and two assembly lines still roll out 3,000 tonnes of steel a

day.

It is the same story elsewhere in Fengrun, a gritty steel town where the

red flag of the People's Republic flies from giant-like loading derricks.

After shutting briefly when steel prices dipped last fall, most of

Fengrun's more than 100 mills have come back to life to exploit a price

uptick this winter, churning out countless tonnes of pipe, girders, rolled

steel and heavy cable.

And that, Mr. Yu says, is the problem: Not that so many mills are going out

of business, but that so many are still going.

China simply makes too much steel. The government estimates that China's

annual production is about 100 million tonnes more than it should be, a

figure equal to the whole annual output of the industry in the United

States.

Worse, China has far too many steel companies, more than 700 at last count.

Add in iron companies and companies that roll or otherwise shape steel, and

the total comes to more than 7,000. Despite repeated government attempts to

force them to consolidate into fewer, bigger companies, most of them are

still small and inefficient.

By rights, many companies should have closed. Instead, they march on like

zombies, China's industrial undead.

That was not such a problem when China was growing at 10 per cent or more a

year and demand was soaring for products made in the “workshop of the

world.” No matter how much steel China made and how many companies were

making it, there was always a market somewhere.

Now it's a problem, and not just for China and its steel makers. In China

and around the world, demand for steel is plummeting. Producers are cutting

back: Japan's output fell 39 per cent and Germany's 31 per cent in February

from the same month last year.

But China's crude steel production in February actually grew 4.9 per cent,

even as steel exports hit a 52-month low, falling 62 per cent on a yearly

basis. Since last October, most steel makers have been losing money. Prices

for Chinese hot-rolled steel fell to about $400 (U.S.) a tonne in March,

less than half the peak of $980 a tonne hit last year. Even China's Iron

and Steel Association has cautioned that overproduction has risked flooding

the market with unwanted steel.

In its latest master plan for steel, drawn up this winter, Beijing says it

will force the industry to slim down and consolidate. But such edicts have

been issued many times before, and instead, production has continued to

proliferate. Few believe this time is likely to be different.

The impact of China's overproduction is being felt around the world. As

demand for steel products plunges, China's continued strong production is

hurting producers in other countries. Just this week, a group of American

makers of steel pipe used in oil drilling filed complaints with U.S. trade

officials alleging unfair competition from Chinese imports they say have

been dumped on the domestic market.

“That is the challenge of China,” says Michael Willemse, an analyst

with CIBC World Markets in Toronto. “They can be very disruptive to the

global market if their capacity-expansion plans are not consistent with

consumption needs of the industrial economy.”

MINERS STILL HAPPYChina's romance with steel goes back a long way. Chinese

in the Han Dynasty, 1,800 years ago, produced an early form of steel by

combining wrought iron and cast iron.

In the disastrous Great Leap Forward of 1958 to 1961, Mao Zedong made grain

and steel production the centrepiece of his plan to surpass the decadent

West. The Great Helmsman encouraged the people to build backyard steel

furnaces in every commune and neighbourhood. To meet wildly unrealistic

production goals, they melted down pots and pans and burned furniture for

fuel.

When Deng Xiaoping abandoned Maoist economics in 1978, China began building

its steel industry in earnest. As foreign investment poured in and the

economy took off, China ramped up production. In the present decade, it has

grown at an average of more than 20 per cent a year. It now exceeds the

combined production of Japan, the United States, Russia, India, South

Korea, Germany, Ukraine and Brazil.

China became the world's biggest consumer and producer of steel, accounting

for a third of the world's total output.

Like the auto industry in North America, steel in China came to be

considered an essential industry, too big to fail. It directly employs 3.58

million people. Millions more live off it in support roles. As of 2007, it

contributed 4 per cent of China's gross domestic product and 9 per cent of

industrial profits.

For a long time, everyone seemed to benefit. Chinese steel makers were

growing and making money. Foreign steel makers were selling lots of steel

to China, which was a net importer of steel until 2006. Iron ore producers

in resource-rich countries such as Canada made a fortune as the steel boom

pushed up prices for ore.

Indeed, the relatively stable demand from China has helped coking coal and

iron prices weather the global economic collapse better than most

commodities – and if Chinese steel makers remain at their current

production levels, that would not be unwelcome to the international iron

ore and coking coal producers.

At a time when financing for most mining firms has all but disappeared,

China has been a lone source of capital, playing sugar daddy abroad to

shore up the future of the domestic steel industry. Last week, Wuhan Iron

and Steel Group Corp., or WISCO, one of China's largest steel producers,

agreed to invest a total of $240-million to acquire a 20-per-cent stake in

Consolidated Thompson Iron Mines Ltd. and a 25-per-cent stake in the

company's Bloom Lake iron ore development project in Quebec.

But for China, the continuing steel push, once a sign of strength, has

become a sign of weakness.

The sector's prodigious growth made it a vivid symbol of China's rise. Now,

it tells the story of chronic overinvestment and overcapacity, manipulated

lending, political interference in markets and overreliance on heavy

industry – faults that are being exposed by the crisis across many of the

country's industries, and that could cost China dearly as the global

recession grinds on.

Steel is not the only industry plagued by too much capacity and too many

companies. China has 5,000 cement makers, 3,800 glass makers, 3,500 pulp

and paper producers, and no less than 24,000 chemical companies.

“It's a kind of a perpetual theme here,” says Jack Perkowski, now a

merchant banker in Beijing who came to China from the United States almost

20 years ago to start a car parts company – and was startled to find

there were already 150 companies making piston rings.

“If you look at any product, there are usually only half a dozen or so

companies making it in most countries. In China, there are hundreds or

thousands making that same product.”

The reasons behind China's capacity issue say a lot about how China works

– or doesn't – and points to a slew of other problems.

Outsiders tend to think of China as a centralized state with an

all-powerful government that can order industries around at will. In fact,

real power often lies with provincial and local officials, the powerful

barons of the Chinese political system.

Like Canadian premiers, they fight among themselves to attract industry.

And steel is a particular favourite, a “pillar industry” that produces

a crucial raw material for many other prestige industries, like automobiles

and appliances. In China, Mr. Perkowski says, “every town and every

village has to have a steel mill.”

The result is a highly dispersed, even balkanized industry, with production

spread around a half-dozen major steel-producing provinces and a dozen or

more smaller rivals. Those provinces compete constantly to outdo each other

at steel production.

The perennial winner is Hebei province, a traditional industrial powerhouse

in northeastern China, surrounding Beijing and the port of Tianjin.

According to the industry watcher mysteel.net, Hebei – where Mr. Yu's

Fengrun mill is located – won the output “championship” for the

seventh successive year in 2008, producing more than 100 million tonnes.

A value-added tax introduced in 1996 gives the provincial barons even more

incentive to lure steel companies and win bragging rights. A quarter of the

revenue from the VAT goes to local governments.

Balkanization makes for massive inefficiency. In a country like China that

lacks high-grade iron ore, the ideal would be to produce steel in big,

modern plants near coastal ports, making it cheaper to bring in ore and

coking coal, and easier to export production. Instead Chinese mills often

have to bring in their ore over hundreds of kilometres of rail track,

pushing up their costs.

Pushing up pollution, too. A report last month from the Alliance for

American Manufacturing claimed that China's steel industry, with its

massive consumption of coal and electricity, produced half of the carbon

dioxide from world steel production, making it a huge contributor to the

greenhouse gases said to cause global warning. It also claimed that

governments help the industry with more than $15-billion a year in energy

subsidies, adding to pollution and overproduction.

China's government-directed banking system plays a part in runaway steel

output, too. In China, the big banks are run by the state. Their local

branches are often closely tied to local officials.

Eager to reap the taxes they get from steel companies, those officials

arrange with banks to provide financing for new mills. In China, where

labour and land is cheap, mills can be built in a fraction of the time it

takes in the West for a fraction of the cost.

If steel prices are rising, they quickly generate handsome profits. But

that adds to China's capacity and, in time, overcapacity. That, in turn,

puts downward pressure on prices. In a normally functioning market, Mr.

Perkowski says, that would lead to an industry shakeout. Weaker, smaller

mills would close. Production would fall to meet demand.

Not in China. With “everyone incentivized to keep producing,” he writes

in his 2008 book Managing the Dragon, “this capacity never closes.

Instead, the plant churns out product at ever-diminishing prices. As long

as it can sell at a price equal to the variable costs of production, it

keeps producing.” Even if it can't cover those costs, friendly banks may

step in to cover its losses.

“This is a topsy-turvy, helter-skelter model of economic growth where

each province has its own plans and the central government just sits on top

and screams,” says Hans Mueller, an independent consultant based in

Tennessee who follows China's steel industry.

The screaming does not seem to do much good. Beijing's latest master plan

would hold crude steel output to its current level of about 500 million

tonnes. It would move more steel-making capacity to the coastal regions.

And it would raise the minimum size of blast furnaces to 400 cubic metres,

up from 300 at present, with the intention of forcing smaller,

less-efficient mills to close.

The aim is to make its industry more like other countries', with a few big

dominant players. China's top three companies account for only about a

fifth of the country's total production, compared with well over half for

the top three in the United States, Russia or South Korea. South Korea, in

fact, gets 87 per cent of its production from just two giant mills.

To bang heads together, China's cabinet set a goal last month of raising

the share of output from its top five steel companies to 45 per cent of the

total from 28 per cent at present.

Canada's Teck Cominco Ltd., a major producer of coking coal used to make

steel, is betting on the consolidation of the Chinese steel industry.

Although it doesn't sell coal to China now, it hopes to in the future once

more Chinese production moves to the coast, creating demand for seaborne

coal.

Selling to China's coastal regions was a key driver behind the company's

$14-billion (Canadian) takeover last year of Fording Canadian Coal Trust

– a deal that has left Teck straining under more than $9-billion (U.S.)

in debt. “It's one of the reasons that we believe in the coal assets,”

said Teck spokesman Greg Waller. “There is going to be a fundamental

change in the valuation of metallurgical coal in the future.”

If history is any guide, it could take a long time for Teck's coal to get

to China's coast. The Chinese “have been talking about this as a matter

of national state policy since 2001 and the number of steel firms went up

and up and up,” says Daniel Rosen, principal of Rhodium Group, a New York

consultancy. “The reality went in a totally different direction.”

In fact, Beijing's massive four-trillion-yuan economic stimulus program

threatens to worsen steel's obesity issue. Much of the money will be used

for steel-gobbling projects like railway expansion. To further cushion the

industry from the global recession, Beijing is raising a rebate on steel

exports.

Yet despite the likelihood of continued Chinese steel overproduction, the

country's growth could very well serve as the cornerstone for a global

economic recovery.

Na Liu, China strategist at Scotia Capital, says China's iron and copper

imports hit record highs in February, and net imports of aluminum and zinc

are at their highest in several years. China's recent willingness to pay

$140 a tonne for coking coal helped support a 2009 benchmark coal contract

of $129 a tonne that was much higher than many expected.

As for steel, low prices coupled with China's relatively high cost of

production may have already tipped the trade balance in favour of imports.

Russian steel producers “have been selling into the Chinese market at

very competitive prices, and China might actually have become a net

importer of steel in March,” Mr. Liu says.

While China's labour and regulatory costs give it a major advantage over

other steel-producing nations, the bulk of those benefits will eventually

disappear.

“Gradually, Chinese steel mills are going to lose their cost advantages,

as environmental protection and other regulatory costs begin to go

higher,” Mr. Liu says.

Back in Fengrun, Mr. Yu knows his industry may need to change.

“When I was a kid, the country's power was measured by how much steel it

produced,” he says.

Now, he complains that the industry has too much capacity and too many

players. “They can't all survive,” he says. “Some of these companies

have to die off.”